The Gainsborough Heritage Association would like to make this blog a special tribute to one of our volunteers, Peter Bradshaw who passed away in March this year after a long battle with cancer. Peter was a dedicated and much-loved volunteer. Before his time volunteering at the Heritage Centre, he worked in Gainsborough as a school teacher for many years at Middlefield Lane School and Trent Valley Academy.

His passion for the First World War changed many people’s lives from students in his classes that he took to explore battlefields and cemeteries in France. As well as people exploring their family history and wishing to learn more about the men buried in Gainsborough’s Cemetery who served in the Great War.

In particular, this blog post has been a difficult one for me to write, as Peter was such an inspiration to me. Writing on behalf of the team at the Gainsborough Heritage Centre, we miss him so much and I know that many other people will feel the same. He was a kind and generous person and his memory will be cherished forever. Rest in Peace, Peter.

Watch the special video below, created in memory of Peter.

Historian and author, Peter researched many sources including the Gainsborough News and located thousands of stories relating to the men and women who lived through the Great War in Gainsborough. He researched and produced five books called Gainsborough’s War Story detailing each year of the War with information on soldiers at the front, women working in the local industries as well as the fabulous work of Gainsborough’s nurses. The books share the historical background of many battles from the Battle of Loos and the capture of the Hohenzollern Redoubt in 1915 to the Somme in 1916. A focus on local stories located in newspapers and letters to old photographs and much more bring these well-known battles to life.

Gainsborough’s War Story Books 1, 2 and 3

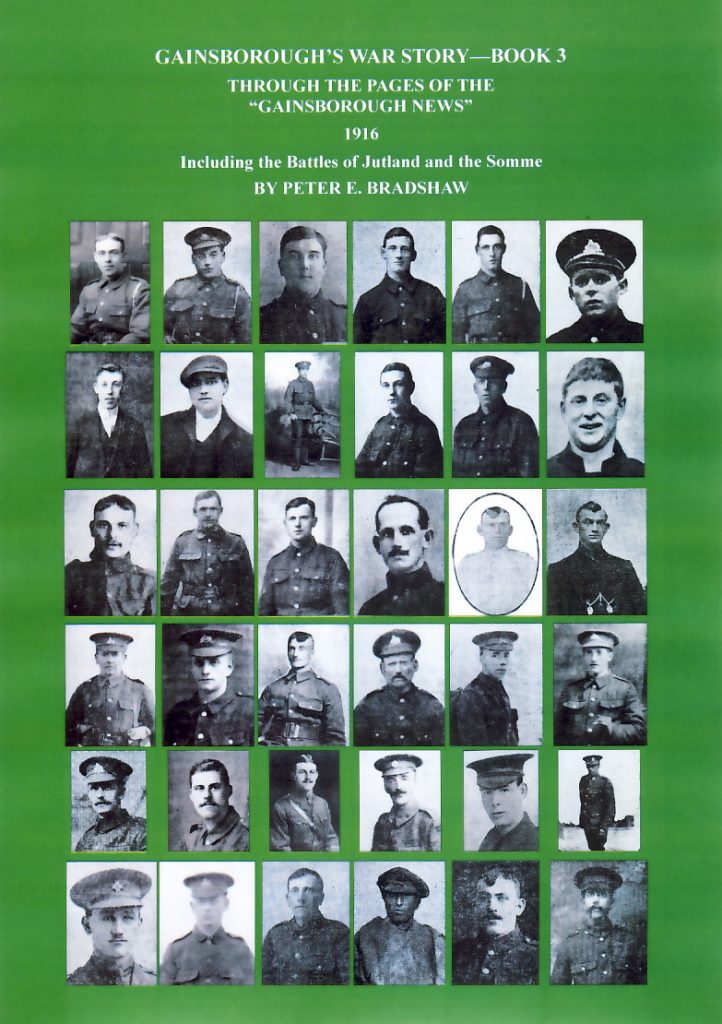

The third book detailed what happened in Gainsborough and surrounding villages during 1916. At the start of 1916 Gainsborough was still mourning the dreadful loss of life of local men at the Hohenzollern Redoubt from 13 October 1915 and at Gallipoli.

1916 was to see two of the most famous battles of World War One, the naval Battle of Jutland on 31 May to 1 June and the Battle of the Somme which started on 1 July. Three of the Snow brothers from Ropery Road were on three different ships that fought at Jutland. Walter and Albert were lost, serving on Queen Mary and Black Prince, sunk with the combined loss of 2,126 lives. Their brother William, serving onboard Diligence, survived.

Thirty-four Gainsborough soldiers were killed in action during the first three days of the Battle of the Somme. During the 141 days of the battle, eighty-seven local soldiers were killed. Half of the local soldiers who were killed do not have known graves and are named on the huge Thiepval Memorial to the Missing.

The book details the exploits of Petty Officer Charles Ernest Cobb, D.S.M., who went from a life of weaving baskets in Church Street to the adventure of taking two motorboats 2,300 miles overland from Cape Town, through the jungles and mountains of Africa, to Lake Tanganyika and taking control of the lake from the Germans.

Throughout 1916 the Zeppelin threat continued. On many occasions, the inhabitants of the town heard the drone of engines passing overhead but Gainsborough miraculously escaped being bombed. Gainsborough’s closest escape came during the raid of 2 to 3 September 1916. Bombs fell in fields at Knaith and several houses in West Stockwith were hit, the inhabitants having lucky escapes. Later in the raid, Retford’s gasworks was hit, resulting in a tremendous explosion and flames.

Gainsborough’s War Story Book 3

As you read further in this blog, there are just a few key pieces of Peter’s research that I would like to share that show just how important his work was in preserving stories from that time before they are lost forever. The First World War for many is starting to disappear from public memory as fewer people can remember the events that occurred at that time. The information Peter located in the old Gainsborough newspapers and archives, or by contacting relatives of soldiers who fought in the War all contributed to fantastic resources of information.

I included helped Peter in the creation of his books as my Great Great Grandad Charles William Clarke was captured in 1915 and served the rest of the War as a prisoner. The many letters that Charles sent back to his future wife May and the story of his life during the War are just one among many which were recorded thanks to Peter.

Peter also worked with the Commonwealth War Graves Commission to ensure gravestones were erected on the unmarked graves of Great War soldiers and organised ceremonies to commemorate soldiers and anniversaries of battles. He worked with Susan Edlington to develop the Friends of the General Cemetery.

In November 2018, Peter unveiled a new war memorial at the Gainsborough Heritage Centre containing the names of 556 men from the town who gave their lives in the conflict. Peter was involved in helping many other groups in the town including the Gainsborough Constitutional Club. You can read the article from our blog about the War Memorial unveilings in 2018.

Peter Bradshaw after unveiling the War Memorial at the Gainsborough Heritage Centre in 2018

Peter helped the staff at Queen Elizabeth High School to research and gather information on the old boys who attended the school and fought in the Great War. To find out more about a couple of the old boys who are named on their memorial read an article published with Lincolnshire Live in 2017 called the Remarkable stories behind the names placed on the new Gainsborough war memorial.

The Lincolnshire Remembrance project was developed to research and create a database for all of the War Memorials across Lincolnshire. Peter assisted the project team with access to his research on the Gainsborough Memorials and was a font of information. The database is now searchable on the Lincs to the Past website.

Peter was well-known for his kindness and help that he would give to people. In a Lincolnshire Live article published on 22 March 2020. Lynne Birkitt, a volunteer at the Heritage Association, told them that teaching and history were Peter’s great loves.

She said: “He loved taking his classes to the battlefields and cemeteries in France. He also dedicated many hours of work creating books to help families find out about their members who fought in the First World War.”

The article continued by saying that Peter was highly regarded by many people in the town. Comments left on social media include “a great teacher and genuinely lovely man”, “an inspirational teacher, dedicated to the core”, “a genuinely lovely man who always had a passion for his job and history” and as someone who “certainly left a legacy with all the people and soldiers you have found to be remembered in your books”. To read the article published by Lincolnshire Live click here.

The Heritage Association has created a digital remembrance book as a tribute to the inspirational Peter Bradshaw. Click on the guestbook link below to sign the remembrance book.

View my Guestbook

Free Guestbooks by Bravenet.com

To comment on the remembrance book then please click the sign button, for your opportunity to share your message. It will ask you for your name, where you are from, how you knew Peter Bradshaw, and then there is the opportunity to leave a special message. Once you have finished your message click submit when you are ready.

If anyone has any problems with submitting a message please just email your message to [email protected] and I will post your message on your behalf. Any messages you leave on this digital remembrance book for Peter will be shared with his family.

Earlier in the blog, I mentioned stories that I would like to share from Peter’s series of books. I remember reading the first book from 1914 and being totally mesmerised by one lady and her story.

Nurse Grace Broadberry

The Gainsborough News reported on 9 October 1914 the story of a Gainsborough Nurse based at Charleroi called Miss Broadberry.

The following are letters sent by nurses at a French hospital-through the medium of the St. John Ambulance Department-to their relatives in England. They are particularly interesting to Gainsborough people from the fact that one of the writers is Miss Broadberry, daughter of Mr. Robt. Broadberry of Silver Street. The letters were brought to us in England by an American, as the nurses are practically cut off from the outside world, “prisoners,” as they themselves state. The letters speak for themselves:-

The Civil Hospital, Marcinelle, Belguim, Sept. 4 1914

Dear Mrs. Oliver, ….N. Boutle and myself came out here ten days ago with Miss Thurston, and we are very busy in the above Hospital. Although we have plenty of work we are very happy, and are quite enjoying our time “at the front.”

We have had many badly wounded soldiers – German, French and Belgians, but now all Germans have been removed.

There were only the three of us for the first week, and the first night Miss Thurston was on alone, and by the condition of everything when we arrived in the morning she must have had an awful time. There are now two other nurses here, and everything is a little more orderly. Miss Thurston has by degrees made many improvements. Miss Thurston was appointed Matron here, and we are working as Sisters now. We have one Sister on night duty, and it is nice to go to the wards in the morning and find things a little shipshape. Before there were no trained people here at all, so you may guess what it was like.

So far, our life in Belgium has been nothing but excitement, but we do not regret coming in the least.

If any of our people should enquire about us we should be pleased if you would let them know that we are quite well and happy.

Yours sincerely,

(Signed) G. Broadberry

Grace’s colleague Elsie M. Boutle adds:-

“We have now been ten days, and for a week there was only Miss Thurston, Sister Broadberry and myself and everything was in an awful pickle. Miss Thurston stayed up for the first night, and it must have been awful for her, as there was not a single trained person here, with about 60 badly wounded soldiers, Germans, French and Belgian. Now all the Germans have been taken away, and some of the French. The latter of course are prisoners. We have very good work here, but do not quite appreciate the Belgian methods of doing dressings, sterilization and asepsis. However, Miss T. was appointed by Matron the second day, and has (with much difficulty) got things a bit ship-shape. We are about 40 miles from the Brussels, and as near the front as possible. Cannon boom night and day. Germans pass frequently, and they always salute us. One German officer who spoke English came to see G. Broadberry, and was quite nice…. We came through Charleroi by automobile, and the place is in ruins. The Germans have burnt the town practically.”

Matron Violetta Thurston wrote on Sept 4:-

Dear Mrs. Oliver, – I do not know whether you ever got a letter I wrote telling you where all the nurses in my charge were placed. I sent it by an American who was going to try to get through the German lines, but whether he ever succeeded or not I do not know. I am writing from Marcinelle, where the big battle was fought 10 days ago, so you see we are quite at the front. I had a message to send three nurses at once to the Burghermaster of Charleroi, who had got an automobile through. I thought it might be dangerous and I could not send three people I did not know there, to do I did not know what, so as all the others were happily placed I came myself with two nurses- G. Broadberry and N. Boutle, from Paddington Infirmary. They have been as good as gold, and I have never heard a single grumble, though there has been a good deal to put up with. The authorities made me matron of the hospital for the time being. It is a hospital that was built 10 years ago and never finished, and is being used temporarily for the wounded. The day we came there were 70 very badly wounded- French and Germans- sent here, and there were only our three selves with some Red Cross people from the town who had attended six lectures, and who nearly drove us quite mad. I wanted to send back at once for some more nurses, but could not for two reasons. First, the Germans would not let us go and fetch them, and there are no trains at all, or posts or telegrams or telephone. We are prisoners here of course, and absolutely cut off… and secondly, they did not want any more people, as there was no food. We have really been almost starved. Fortunately we had each a little private store, and I think that any one else coming out should be told to do the same (my fountain pen has run out and there is no more ink). There was no bread at first, though we have some more now, no butter, no meat, no milk except for the illest patients. There was practically nothing for anyone the first few days except beer and potatoes and leeks….the nurses….were dreadfully overworked, and our having nothing to do anything with made it much more difficult. There was no water laid on, hardly any sheets or shirts or ward furniture. How we longed for some of the things all the working parties in England were making. Now things are much better. The authorities have been awfully good to me, and allowed me to reorganise the hospital and get it all onto the proper working order. And we have managed to get enough food now for the patients and the staff, and the work is divided up, and everyone happy. The worst cases have died, and the Germans have carried off their wounded, so we have only the French left. Dr. Wyatt heard that we were very pressed, and yesterday he sent two more nurses who are not of my party at all Nurse Campbell and Nurse Sartorius. If we get with it now, and I expect we shall … as the cannons have been going without ceasing for 24 hours quite close, though we don’t know in the least what is going on… As soon as things quieten down here I will put someone in my place- Miss Broadberry probably and go back to my flock in Brussels, who must be feeling rather deserted… This hospital is in the most beautiful position, right at the top of a hill with a very extended view in every direction, but Charleroi is a very sad place now. Nearly all of it is burnt down and pillaged by the Germans… There are many streets in which every single house has been burnt down. We get no news at all… There are some 2,000 Germans quartered in the town, all their rules and regulations which we all have to obey are very tiresome. For instance, no window may be open and no shutters may be shut (this is in case people shoot at them from the windows). I hate sleeping with my window shut. Happily we do feel that we are of real use here, and the people are so grateful and so glad to have us. I am very glad we came. The patients are dears too, and so grateful…

On January 1, 1915, the Gainsborough News reported on the story of Miss Broadberry, a Gainsborough Red Cross Nurse at the front as her story developed.

Miss Grace Broadbery sends us the following interesting letter:-

As I had such a short time in Gainsborough I could not see all the people whom I should like to have seen and who would have liked to have heard about the times I had “at the front,” so I thought I would ask you to put it in the “Gainsborough News” and then all could read it.

I was a Ward Sister at Paddington Infirmary and heard that nurses were badly wanted in Belgium, so I offered my services to the British Red Cross Society, and was accepted, and at very short notice was sent to Belgium in August with a party of nurses. We left London on August 19 with about 80 nurses and proceeded to Brussels, which was reached the next night. We found on arrival that we were not excepted, as a cable had been sent to stop us, as the Germans were already on the outskirts of the town, but it had failed to reach us in time. The whole party went that night to the Hotel Metropole, Brussels, and the Matron, saw how serious everything was, and said that if any nurse wished to return, she was at liberty to do so, as the Germans were expected any moment, and, of course, if they should arrive, we should be their prisoners. Some of the party accordingly went to the station, but alas! They were too late, the lines were already cut. We slept at the Hotel that night and the next morning the Matron told us that the Germans were already entering the town, and we were told off for ambulance duty at L’Hospital S. Pierre. As we walked through the town we saw the Germans marching through the streets singing. We remained in Brussels for one week visiting several hospitals but there were no wounded soldiers, only a few tired Germans. As we daily went from one hospital to another we met thousands of Germans, but we did not take any notice of them. When we had been there one week, the Matron asked my friend and myself to accompany her to Charleroi, which is a large mining town in the centre of Belgium, as the Germans had commandeered three English nurses to go there, so we three were taken to Charleroi by motor (about 70 miles). As we went through Jumei and through the outskirts of Charleroi, the whole of these villages were in flames, and the poor Belgians were running along the road with bits of furniture which they had tried to save, as their houses were burning to the ground. We went to Marcinelle, about two miles further on than Charleroi, to a hospital there. There were no nurses there, only a few Belgian ladies, and the wounded were just coming in from Mons, Gozee, Malines, etc. Well, there were just the three of us for 70 wounded German and French soldiers. All the soldiers had more than one wound and some had as many as eight, and all were in a terrible state. I don’t think any of us will forget all we saw at that time. The poor men had been lying two or three days wounded on the battle fields before they were brought in, and some had been shot many times because they were unable to drag themselves out of the firing line.

After three weeks our Matron left us to see the other nurses in Brussels and two other nurses came. The German doctor came every day and after about 10 days of real hard work, and not knowing what to do at first, the German soldiers were taken away. They were removed just as they were, it did not matter how bad they were. One man had undergone amputation of the leg at 4p.m. on the previous day and was also taken away. Needless to say he died half-an-hour after he left the hospital. Another man was very ill with pneumonia, and a bullet wound through the lungs, also had to go, and even to walk to the ambulance. What became of him we did not know, and there were many others very ill, but all had to go. Three died on the way to the station. The Germans told us that they were taking them away because they were home sick. The French wounded were left, and the German doctor came every week to see how they were getting on and to take away all who were fit to be moved. Eventually the patients were reduced to four bad cases, and after an interval of one week the German doctor came early one morning and said they were all to go, and really there was not a man in a fit state to be moved. After all our wounded had gone we did not wish to stay to be a burden to the people, although the directors of the hospital were very good to us and said we could remain as long as we liked but we knew quite well that they had very little food and already for about six weeks out of the 14 we were there we had lived on leeks, potatoes, beer and black bread, which we could only get once in ten days, so we thought our best plan would be to come home, and go out later if necessary. So we boldly applied for passports to leave Belgium. The German doctor was very nice and filled them in for us, but the Commandant would not sign them. We asked him why, and he said “Because we were English, and were prisoners of war and must abide by it.” So we went back to the hospital and remained there for several days and then we again applied, but were told “No.” The Commandant said he would not give us permission to ride even round Charleroi. We received a letter from our Matron but could not make anything of it as all the information had been torn off by the Germans. We got very nervous about being there in that unprotected state and for a month we never went out at all, and we never knew what the Germans would take into their heads to do to us as they constantly came and took away what little food we had, so we had to hide all we could. We then thought we would try to escape, it was very risky, but we felt we would do anything to reach England. So we started with false cards of identity and went from cart to tram for three days, right through Namur and Liege, etc., meeting everywhere crowds of Germans, but we left all we had and disguised ourselves as French or rather Belgian peasants, and as peasants, supposed to be travelling into Holland to buy food for the Germans to live on we passed right through the German lines. At one sentry box we were covered with the gun for fully three minutes, thinking every moment would be our last. But we managed to keep our heads and as peasants we were allowed to pass. One who was too tall, and we were afraid to let her walk across with us, because she was very tall, passed over the Dutch frontier, posing as an idiot. After these risky and exciting experiences we came home (being on the way nearly one week), via Flushing, and passed two floating mines. We were not sorry to see Folkestone.

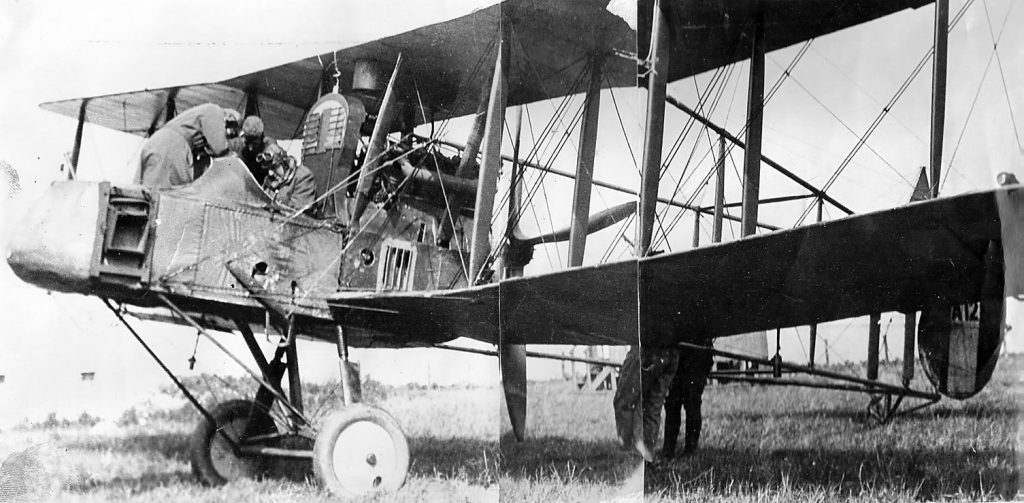

Peter raised awareness of his research and the fascinating stories he had uncovered with informative and enthusiastic talks. One talk delivered by Peter in 2017 saw him share stories from a time when Zeppelins were seen over Gainsborough during the First World War and the role of the Royal Flying Corps in defending the realm against this new German menace.

The talk focused on the Zeppelins which passed over Lincolnshire during World War One and the work of 33 (Home Defence) Squadron whose headquarters was in Gainsborough from the autumn of 1916.

Zeppelin

Peter shared information about how the people of Gainsborough got used to the sound of Zeppelin engines passing overhead during the night. Throughout the country there was a dread of the risk of being killed in your own home by these terrifying new weapons. It took a while before the importance of a complete blackout was accepted. In 1915 the “Gainsborough News” regularly published lists of locals who had been fined for not observing the blackout. It was only when local towns such as Scunthorpe and Cleethorpes were bombed and there was loss of life, that local people took the blackout more seriously.

It was only after the war had ended that the “Gainsborough News,” in 1919, revealed that in the early hours of Sunday, September 3, 1916, the town had a very narrow escape from being bombed during a raid. The first bomb, which fell about midnight, made a huge hole in a wood at Knaith. Then lights at the works at West Stockwith attracted the Zeppelin and nine bombs were dropped, some of which did a good deal of damage to house property at East Stockwith, and shattered windows at West Stockwith. The works escaped. No one was killed but one woman in her eighties was in bed and would have been crushed by the falling roof but for the fact that one of the beams became lodged over her head. Bombs were also dropped on farm land at Morton Carr. Later Retford was bombed and the gasometers were hit – the flames from the explosion were visible in Gainsborough. Many properties in Retford were damaged and several people were seriously injured.

By the middle of 1916 criticism of the failure of the government to prevent the raids led to changes in defences. It was decided to move Home Defence Squadrons closer to the coast with the aim of intercepting the Zeppelins earlier. This led to the Headquarters of 33 Squadron being moved from Tadcaster to Gainsborough. The Royal Flying Corps took over “The Lawn,” a mansion on Summer Hill, as H.Q. and part of the Workhouse was taken over as billets for mechanics. An airfield was established just across the river from Gainsborough. Canadian officer, Lt. Arthur Menzies, wrote home to his parents describing how local people would walk across the bridge after work to watch the planes taking off.

FE2d A12 – the plane that Canadian Lt. Menzies was in when it crashed at Elsham on 25 September 1917 during a Zeppelin raid. He is buried in Gainsborough

Three main airfields were established at Manton (Kirton-Lindsey), Elsham and Brattleby (Scampton). The pilots who came to the HQ at Gainsborough were from all over the Empire – Australia, Canada, New Zealand, South Africa, Argentina (not part of the Empire but it had strong links to Britain). Some of the pilots had survived action on the Western Front and were brought back to England because their experience was needed to try to combat the Zeppelin threat. Others were newly qualified pilots. But flying at night was new and was dangerous. There were numerous accidents. During the two years 33 Squadron was in Gainsborough, fourteen officers were killed. The first casualty was Canadian, Lt. Don Brophy, a very experienced pilot – against the odds he had survived for several months flying on the Western Front but was killed in a flying accident at Kirton Lindsey a month after returning to England. He is buried in the General Cemetery. None of his relations could attend his funeral. Seven other officers were buried close to him during the following months. One of these was South African officer 2nd Lt. Laurens Jacobus Van Standen, who married local woman Emmeline Beilby, on 2nd February, 1918, but only twelve weeks later was killed in a flying accident.

Another talk hosted in 2018, by Peter covered two topics – the Morton Gynes disaster in 1915 and the Shell Filling Factory which was built at Thonock in 1917.

In October 1914 over 4,000 Yorkshire Territorials came to Gainsborough to carry out training before being sent to France. On Friday, 19 February 1915, the town was shocked when seven members of “D” Company of the Fourth Battalion, King’s Own Yorkshire Light Infantry were drowned. They had gone to one of the gymes (ponds) in Morton, to practice raft building. Estimates of the number of soldiers on board the raft when it tipped over were disputed, some claimed that it was up to 40. Within seconds dozens of men were in the cold, deep water, wearing their heavy uniforms and boots, struggling to survive. Within days of the tragedy the K.O.Y.L.I was removed from Gainsborough and sent to York. By April 1915 they were in the trenches in Northern France. In June Captain Harold Hirst, who had been in charge on the day of the drowning, was shot and killed by a sniper.

Morton Gynes

In November 1917 building started on a 149-acre site at Thonock for the National Filling Factory No.22. It was built to fill mines for the navy. By February 1918 the first “Sinkers” had been filled with 1000 lbs. of TNT (trinitrotoluene) and were sent to Portsmouth. By the end of the war, the factory had used over 2476 tons of TNT. The factory had reached full capacity just as the war ended but it went on for several more years decommissioning munitions and it was the mid-1920’s before the land reverted to farming.

Peter will always be remembered and his books are a testament to his hard work. Thank you for reading this special blog and please leave a message on our remembrance book to share your memories of our friend, Peter.

Comments(13)

Alan Draper says

26th July 2020 at 10:13 pmI met Peter on a number of occasions and he was always happy and eager to discuss any ancestors that were involved in the war. We both attended the 100th anniversary of the Honzoloron redoubt . A lovely man who would always remember you and have a chat.

Sheila Horner-Gkister says

27th July 2020 at 8:59 amI knew Peter through my late husband, Peter. My husband was caretaker at Middlefield School. I saw an article on Facebook about a Great Uncle of mine. Although my family originate from Brigg, this Uncle was landlord of one of the pubs in Blyton. I mentioned this to Peter and within days he was back with the Great Uncle’s history!. A wonderful man.

Michael Hatfield says

27th July 2020 at 7:53 pmI worked with Pete for many years at Middlefield School and Trent Valley Academy. A kinder, gentler man you could not hope to meet. But he was an inspirational teacher, a passionate historian, a caring teacher and a fabulous colleague,too. As a school leader, he was honest, committed, hard working and reliable: a true role model for both staff and students. He will be missed. But his legacy lives on in our hearts and the achievements of the children he taught. There were exceptional young people from Middies and TVA who owe their love of History to him. That is his real tribute: he made a difference! Rest in Peace, Mr Bradshaw. Your work is done..

Janet Thorpe says

27th July 2020 at 9:37 amWhat an inspirational tribute to an amazing historian and a lovely friend. At QEHS, we could not have managed to put together our profiles on the Old Boys who died in WW1 for our new War Memorial or been able to help families of ex students who were in The Great War, without Peter’s unstinting support.

A moving blog which I will pass on to his other friends on the school staff.

Thank you, Gemma.

Liz Clews says

27th July 2020 at 10:02 amPeter was a smashing presenter for the Ladies of Morton WI. A very interesting talk on our local churches and the headstones. His knowledge was second to none about many elements of Gainsborough’s local History. The War Memorial at the Gainsborough Heritage Centre is amazing. A lifetime of work that will be passed down in generations. Peter will be sadly missed.

Michael and Carole Hatfield says

27th July 2020 at 3:22 pmAs colleagues who worked with Pete both at Middlefield School and Trent Valley Academy, we would just like to share our love and respect for him both as a teacher and as a person. He was decent , honest and kind to everyone, and was passionate and really cared about his subject. In short, everything you’d want to see in a teacher, or in a friend . His inspiration lives on, because everyone who knew him will remember him fondly. We are proud to have had the opportunity to work with him. He was the best of England, and passed that spirit to us all.

Clare lidgett says

27th July 2020 at 5:22 pmA great history teacher at Middlefield School and had time for all his students it was so nice to see him at my visit years later to The Heritage Centre were he saw me and said Hello Clare I was touched to think he remembered me r.i.p.Mr Bradshaw.

John Steel says

27th July 2020 at 5:36 pmMet Peter when invited to Middlefield school with some of my WW1 collection, and found a kindred spirit. We shared information and he readily offered help when I was researching Marshal Aircraft. He had a vast depth of local WW1 knowledge and always happy to help. He has left a great gaping hole in local history research and his books will remain testiment to his passion.

Laura Delleur says

27th July 2020 at 6:55 pmPeter you inspired more than a generation. I was lucky enough to work with you and we took hundreds of children to France. They loved and were inspired by your passion and expertise. Personally a friend and colleague I will never forget. An amazing legacy created by a wonderful man who always did it for others. Rest in peace dear friend x

David Fell says

27th August 2020 at 3:12 pmI am very sorry indeed to hear Mr Bradshaw has passed away. I corresponded with him occasionally about 33 Sqn during WW1 at Elsham Wolds. He was a most knowledgeable and helpful gentleman

Mark Binns says

15th September 2020 at 6:26 pmPete was my history teacher. He made history very interesting and I would look forward to history lessons. I became a friend of his after school and sometimes would talk about the World War One trains that came into or through Gainsborough, no you have gone to meet the soldiers you wrote about Rest in Peace my friend

Ian Megahy says

16th November 2020 at 7:34 pmMy apologies for the late contribution, I only recently learnt of Pete’s death. I came to Gainsborough in 2006 to lead the merger of Middlefield and Castle Hills schools into a new academy. From the outset Pete was warm and welcoming and became a key player in the senior leadership team as we planned and successfully opened the new organization. As a colleague, he was a joy; loyal, intelligent, supportive and wise, whilst treating all staff with respect and consideration. The same qualities shone through in his teaching, where his enthusiasm and passion for history inspired thousands of young people over the years. Perhaps most importantly, however, he left all of us with an excellent example of how a human being should live their life. Thanks Pete.

Tony DUNLOP says

17th December 2020 at 10:17 amI was greatly saddened and shocked to find that Peter had passed away in March this year. I led a WWI project in West Yorkshire which had the objective of remembering the men from Batley and Birstall who were lost in the Great War. The Morton Gymes Tragedy of 1915 was a significant part of our work during 2015. Through our research into the circumstances of the drowning of the seven young King’s Own Yorkshire Light Infantry at Gymes I came into contact with Peter. We worked closely with Peter and two of the ‘moments’ of our five year project came about through our work together. On February 19th 2015 we held a special service at the grave, in Batley Cemetery, of one of the soldiers lost. Around the grave were eight Wreaths. At the end of the service one Wreath was left at the Graveside and six others were taken from there to the graves of the other six men in Cemeteries in Dewsbury, Wakefield, Morley and Harrogate. The final Wreath was taken to St. Paul’s Church in Morton for a service on Sunday February 22nd 2015. Over 20 people travelled from Batley to Morton and we were met by a Church that was full to capacity. It was a truly memorable week. Peter was a joy to work with and I know he was greatly regarded in his home area. I have now moved on to writing ‘little books’ (A6 size) and have always planned on preparing one on the Morton incident. Today I set out to make contact with Peter again …. sadly …. but the book will be prepared and it will now be dedicated to his memory. Rest in peace, Peter … we will remember you.

Recent posts

Events