Lincolnshire is known as an agricultural county and is in part naturally separated by the River Trent divorcing its largest market town, Gainsborough, Torksey and the City of Lincoln from Nottinghamshire. East of the Lincolnshire Wolds, in the southern part of the county, the Lincolnshire dialect is closely linked to The Fens and East Anglia where East Anglian English is spoken, and, in the northern areas of the county, the local speech has characteristics in common with the speech of the East Riding of Yorkshire. This is largely due to the fact that the majority of the land area of Lincolnshire was surrounded by sea, the Humber, marshland, and the Wolds; these geographical circumstances permitted little linguistic interference from the East Midlands dialects until the nineteenth century when canal and rail routes penetrated the eastern heartland of the country.

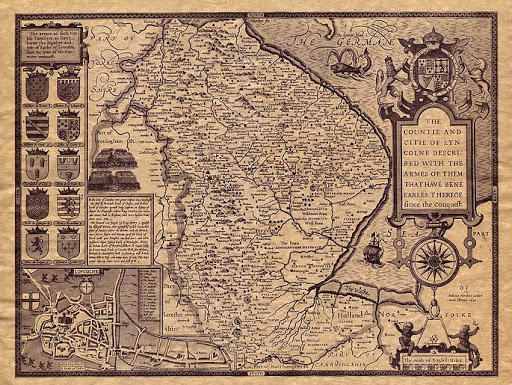

Map of Lincolnshire from 1610

Dialects and accents have developed historically when groups of language users lived in relative isolation, without regular contact with other people using the same language. This was more pronounced in the past due to the lack of fast transport and mass media. People tended to hear only the language used in their own location, and when their language use changed (as language by its nature always evolves) their dialect and accent adopted a particular character, leading to national, regional and local variation.

Scratch the surface of any town or village in Lincolnshire, and it’s likely that the Danes, or their fellow north Europeans, have had a hand in the founding, naming or development of it. The county saw many waves of immigrants during the six centuries following Roman rule, although there is still much debate as to whether they came as mercenaries hired by local rulers who then took over, or as raiders arriving by sea to take what they could, or as settlers moving into relatively uninhabited areas. The answer is probably all three, at different times and in different circumstances. The Saxons were here as Roman mercenaries as the empire declined, and their influence grew, more or less peacefully, as friends and families joined them. More belligerent groups from Scandinavia, mainly Danish, arrived later, and the extent to which they dominated the county is clear from their influence on village names.

Invasion and migration also helped to influence dialect development at a regional level. Just take the Midlands, for example. The East Midlands was ruled by the Danes in the ninth century. This resulted, for instance, in the creation of place names ending in “by” (a suffix thought to originate from the Danish word for “town”), such as Thoresby and Derby, and “thorpe” (meaning “settlement”), such as Ullesthorpe. The Danes, however, did not rule the West Midlands, where the Saxons continued to hold sway, and words of Danish origin are largely absent from that region.

The overall history of settlement in Lincolnshire can still be traced by its place-name, with newcomers establishing villages, or changing the names of the ones that were there already. We don’t seem to have a Lincolnshire equivalent of Torpenhow in Cumbria, which means ‘hill hill hill’ in three successive languages, but we do have other linguistic mixes, including the city of Lincoln itself.

The Romans

Lincoln is a fairly straightforward derivation from the Roman name Lindum Colonia. A Colonia was a settlement for retired soldiers – a kind of Chelterham-by-Fen – but Lindum itself is probably a derivation of a pre-Roman name possibly meaning ‘(place) by the pool’. The place names Caistor, Ancaster and Casterton all show Roman influence, Old English caester denoting a Roman fort or encampment, although both Ancaster and Casterton carry later additions that indicate they were close to a Roman camp rather than a continuation of it; so Casterton would be a homestead by the old camp, and Ancaster could indicate that the owner of the land around it was a man called Ana or Ane.

The ‘Danes’

The biggest influence on Lincolnshire place-names came from the Norse or Old English of the residents in the centuries after the Romans left. Languages developed from the assorted Scandinavians who followed them into the county, usually lumped together as ‘The Danes’.

The Danelaw

Under the Danelaw, which was established in the late ninth century, Lincolnshire became an important centre, the towns of Lincoln and Stamford being two of the five boroughs of that administration. Danish rule eventually fell to that of the English in the early tenth century but, although historians report that much fighting took place, the change was probably of little significance to anyone but a few administrators and the upper classes. The average fenman would hardly have noticed it at all, being already well established in the continuing belief that the less he has to do with the ruling classes the better.

Gainsborough’s history predates Roman times, but it was probably the Anglian ‘Gainas’ tribe who in the 6th century first settled on the site of what is now the present-day town. The earliest notice of Gainsborough, or Gainsburgh, was during the Saxon era. During this unsettled and war-like period it was the scene of various battles, sometimes forming part of the Kingdom of Northumbria, and at others being part of Mercia. Gainsborough’s position on the banks of the river Trent made it very much a frontier town, and when Sweyne (Forkbeard) King of Denmark brought his vessels up the Trent in 1013 and landed his forces in the town, the whole of Northumbria, together with Lindsey, submitted to his rule.

The town became the capital of the country, and also Denmark, for five weeks in 1013. The Dane Sweyn Forkbeard, together with his son and heir Cnut (Canute), had arrived in Gainsborough with an army of conquest. Sweyn defeated the Anglo-Saxon opposition and King Ethelred fled the country. Sweyn was declared King of England, and he returned to Gainsborough. Sweyn and Cnut took up high office at the Gainsborough Castle (on the site of the present-day Old Hall), while his army occupied the camp at Thonock (today known as Castle Hills). But King Sweyn died (or perhaps was killed) five weeks later in Gainsborough. His son Cnut established a base elsewhere. David Childs in an article to BBC News in 2013 stated that he believes the Lincolnshire town could also have been where Sweyn’s son, Canute, attempted to hold back the waves of the Aegir – a tidal bore, which takes its name from the Viking God of the Sea. The Danes were eventually defeated by the Saxons, led by Ethelred. At this period the Danes greatly outnumbered the English.

Although the Domesday Survey of 1086 recorded only eighty people living in Gainsborough, the town grew, and during the Middle Ages emerged as a major wool centre with a thriving port until the advent of the railways in 1849.

Borough is known as a ‘fortified place’ or a ‘stronghold’ from the Old English burh or dative byrig. Gainsborough was a stronghold of a man called Gegan. Torksey was known as an island, raised land of a man called Turog.

Lincolnshire has more place-names ending in –by (from Old Norse by), indicating a farmstead or a village centred around that farm) than any other county in England, with at least 205 villages or hamlets carrying it, from Aby to Wrawby.

Axholme is a large area in the north of the county which is virtually surrounded by the rivers Trent, Idle, Humber, Yorkshire Ouse and Don. Its name may come from the village of Haxey, or share the same meaning: ‘island of a man called Hakr’. Holm/ey ‘island’, ‘raised land in a marsh’ (from Old Norse, holmr; Old Norse ey or Old English eg)

The Lincolnshire flag’s colours represent four reasons why ‘Yellowbellies’ are proud of Lincolnshire. The red cross represents England, borrowing from the Saint George’s Cross which has been associated with the country since the 13th century. It is also featured on the Coat of Arms for the City of Lincoln, which dates back to the 14th century. The City’s Coat of Arms, like the Lincolnshire Flag, also has a fleur de lis in the centre. The fleur de lis is the symbol of the City of Lincoln, featured on its Coat of Arms and emblazoned across the city. This relationship derives from the Diocese of Lincoln: the fleur-de-lis is the symbol for the St. Mary, patron saint of the city and Lincoln Cathedral.

Lincolnshire produces 12% of the UK’s food, and food and farming is the biggest economic industry in the county. Therefore, yellow represents the variety of crops grown in the county. A second reason for yellow is the nickname “Yellowbellies” given to people born and bred in Lincolnshire. The blue parts of the background represent both the sea of the East coast and the ‘big skies’ across the county. The Lincolnshire coast is responsible for 70% of the UK’s fish and boasts a range of stunning natural coastline as well as exciting seaside resorts.

The county’s mostly flat topography means that there are often beautiful landscapes of blue skies to enjoy. The flat land and big skies also give a reason behind the county’s aviation heritage: the perfect environment for runways and air traffic control. The trails of the Red Arrows are often seen left behind! The green background symbolises the fields of the Lincolnshire Wolds and the Fens. The county is known for its beautiful landscapes – of big skies but also rolling hills. You are never far away from a beautiful, green view; even in the heart of the town.

Yellowbellies

I was born in Lincolnshire so I always refer to myself as a yellowbelly.

But what does it mean, and where has the word come from?

According to Alan Stennett’s book, it is possible that the term refers to the yellow waistcoats and uniform frogs (fasteners) worn by the Lincolnshire Regiment, or to the undersides of coaches that were painted yellow and that used to travel to Lincoln. Another suggestion is that market women kept a separate purse for gold coins tucked into their skirt waists, or had a special pouch for them in their aprons so that a good trading day would result in a golden, or yellow, belly, but why that should be peculiar to Lincolnshire is not clear. The same applies to the idea that farmworkers in the fields acquired a brown back, but that constant bending to their work meant that the belly was less tanned, and looked yellow by comparison. Sheep might have got a yellow belly while grazing in flowering fields of mustard, but since that would result in a sharp drop in yield of mustard seed, they would probably have been chased out again long before they had a chance to change colour! That staple of Lincolnshire farm food, the cured ham or bacon has been suggested that someone who was offered a slice took offence and applied the term to his hosts!

Many ideas related to the Fens and a name given to the fen dwellers could have become attached to Lincolnshire folk in general. Most people still think the county is all flat fens; so it would be an idea that might readily spread. Fen dwellers, like yellow-bellied eels, frogs or newts, were seen as spending their time in mud and water. Of these options, newts – particularly the great crested newt, now rare, but once common in the Fens – get a lot of support.

People living in the Fens were also keen growers and users of opium, to help them to fight off malaria which was endemic in the area. The medication can turn the skin yellow if used to excess. The final, and, to some people, the most convincing suggestion, however, is that the term came from Lincoln Diocese’s Elloe Rural Deanery, covering the Fens, which took its name from the Saxon administrative division (wapentake) known as Ye Elloe Bellie.

References

- Nobbut A Yellerbelly! A salute to the Lincolnshire Dialect by Alan Stennett

- BBC News Article called Sweyn Forkbeard: England’s forgotten Viking king by David McKenna (2013).

- Visit Lincoln, What is the Lincolnshire Flag?