The Industrial revolution speeded up the creation of many inspiring and innovative patents that changed the world that we live in today. The first of many developments that changed the world was Thomas Newcomen’s invention of the beam engine the first-ever practical steam engine invented.

William Rose born in Gainsborough on 14 November 1856 grew up in the ever-changing world of the industrial revolution. William worked first as a riveter’s assistant at the age of eleven, and then later became a barber’s assistant. In 1867 when William was eleven years old the government at the time was improving the many laws that governed the industry of factories. William would not have known at that point in his life he would one day be running his own factory and also be developing major ideas that would go down in history. The Factory extension Act was one of many that improved many of the industries that were developed throughout the industrial revolution and its key policies were to restrict the hours during which children, young persons, and women are permitted to labour in any manufacturing process conducted in an establishment where fifty or more persons were employed

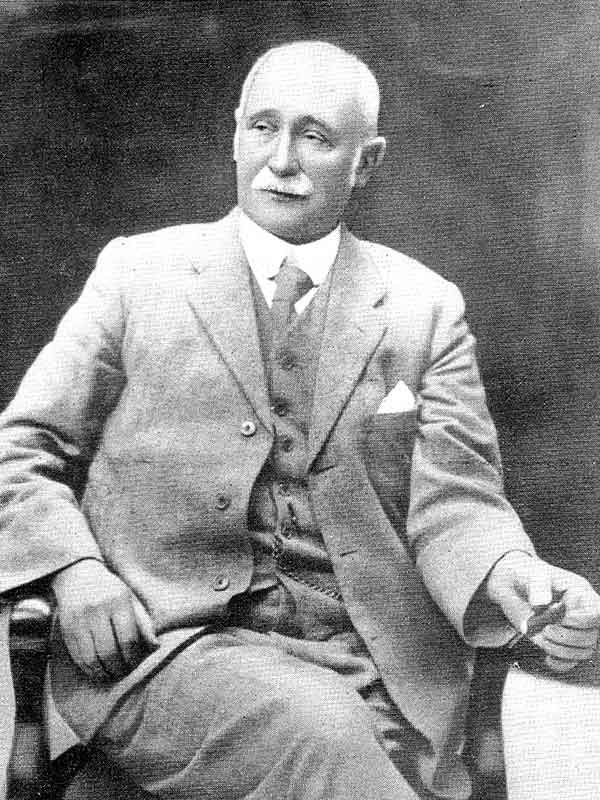

William Rose

As William Rose was growing up living in the industrial concerns were changing. William was only a boy when he came up with his innovative plan to improve the sale of tobacco. During his time working in the barber’s shop, William first saw the need to sell tobacco in packets. When a customer called for tobacco, the lather-boy had to dry his hands and run to the counter to weigh it out by hand and wrap it and he wondered why it could not be sold in packets instead of loose. He resolved to make a Tobacco packaging machine.

William also showed the world how working hard and with determination, you can teach yourself and change how things have been done before. He would work in his bedroom until late into the night and at weekends, he taught himself the rudiments of mechanical drawing, applied mechanics, mathematics, and all the other skills required to develop complex mechanisms – he devised a machine that could quickly wrap half-ounces of loose tobacco into neat cylindrical packages. Trained engineers of later generations marveled at his ambition and tenacity. It was said that he could hardly have started with a commodity more difficult to pack than tobacco. Sweet wrapping machines are much simpler mechanisms than the original tobacco packer with which William Rose “established the basic principles of automatic wrapping of later years”.

William Rose’s original wrapping machine, for which he took out a provisional patent in 1881, was for packs of tobacco, which had previously been weighed and wrapped by hand. This development was looked on as something of a miracle, tobacco being the first commodity to be mechanically wrapped for sale.

After becoming the owner of the barber’s shop, he continued to work at his models – “with neither equipment nor resources, only mechanical problems, financial troubles – and heaps of ridicule”. It took seven years of effort before he completed a machine that did what he wanted, and he took it to the old-established tobacco firm of Wills in Bristol. This proved a very wise move as in their joint names, a patent was taken out in 1885 (Wills later renounced all claims to the patent rights).

A chance visit to a London tobacconist by an American who was taken aback by the sight of a pile of Rose’s neatly wrapped packages, started William on a whirlwind development that involved Richard Harvey Wright (the American visitor), agreeing on a contract which gave him exclusive right to sell, manufacture, the lease on royalty and otherwise handle the Rose Tobacco Packer in the USA, Canada, and Cuba. A clause in the contract required William to adapt his machine to produce rectangular packets for the American market and soon, William Rose had grown out of the premises formed from two bedrooms knocked into one and had fifty men on his payroll in a new factory built on the banks of the River Trent.

By 1905 he had sold machines to the value of over £36,000, his profits for the year topping £3,000. In 1906, William and his brother incorporated themselves as Rose Brothers (Gainsborough) Ltd. Within a few years, Rose began to apply the principle of this machine to the wrapping of other products. Rose Packaging machines were to be found in chocolate and confectionery, bakery, biscuit, and tea factories.

He was able to develop a cigarette packer and was approached by John Mackintosh of Halifax with an experimental twist-wrapping machine for confectionery which he perfected and was then allowed to exploit (the early machines were for toffee fed by hand into the cut and wrap machine). He set aside a special section of his works to manufacture cartons for Reckitt & Sons of Hull. This operation grew rapidly and William formed the National Folding Box Company with his son-in-law Hugh S. Ridley became manager.

Ron Cawte born in 1935 completed his national service and then worked for a few months in the National Fitting section of Roses and then moved to Portsmouth to work as a draughtsman however, this was only for a short time as a job opportunity arose back at Roses. One of his roles saw him as a manager in the carton section and then he worked on confectionary machines. In an interview for the Oral History Archives in 2018, he explained how a toffee machine 42 worked. ‘The rope came in down the side of the machine that’s the toffee rope that has to be presented at the right dimensions and then the toffee gets pushed through into paper that had to be previously folded down. This would then get pushed into the wrapping reel and the big blade closes in and then a tube of paper gets enclosed around the product and on twisting machines, it would be slightly different as the machine would then twist the end of the wrappers. The speed of the sweets that could be produced and wrapped a minute would depend on the condition of the rope so it was important to maintain the rope. It was also quite a stressful role to ensure the machines lived up to the standards for example a machine that could wrap 1200 sweets a minute needed to be looked after otherwise, the machine would wear out in no time at all. This particular machine the 42 was a robust machine.’

The below video demonstrates how a Rose Forgrove 42 cut and wrap machine with a vertical batch roller rope sizer actually works. The Heritage Centre had a machine on display for many years after the redevelopment of the permanent displays in 2016; unfortunately, it has had to go back to its original owner a few years ago. However, Ron visited the museum a few years ago, and upon seeing the machine recalled many memories of his time working at Roses.

Ron worked with the firm of Roses till the 1990s and he recalled his working days as being the happiest days of his life and he thoroughly enjoyed working at the factory. William Rose’s amazing inventions are not just part of industrial history and Gainsborough’s story but also created many jobs and careers for many people like Ron who loved working at this factory. Throughout the year we will be sharing more industrial stories and more of Rose’s history including a blog on Rose’s War Production and more memories of people’s working life at the factory from the Oral History Archives.

References

- Baker Perkins Historical Society on the History of Rose Brothers (Gainsborough) LTD.

- Gainsborough Heritage Association Oral History Archive, Ron Cawte, 2018.