Albert Bernard Moden was born on 23 February 1918. He was born into a very large family and was the fifth son and tenth child of Joseph and Agnes Moden. Known to people as Bernard throughout his life, he was born in what was a very uncertain time for Britain. Britain had just faced four years of war against Germany and many people had died. His eldest brother Frederick James aged 24 in 1918 and another brother William aged 18 was away fighting in the army when Bernard was born.

Sister Alice Ruby with Bernard Moden

Brother Frederick James (left) and brother William Moden (right). Photos were taken during the war years 1914 – 1918.

Bernard was also born at a time when women were at the forefront of helping the war effort in the factories at home. His sisters Elsie aged 21 in 1918 and another sister Elizabeth May aged 16 were both working on munitions for the war effort. They worked alongside their father aged 45 at the Gainsborough factory of Rose Brothers. Bernard’s eldest sister Louise aged 25 was married to Bernard T Hird, however; she was living at home when her youngest brother was born due to her husband being away at the front also serving in the army. He was doing joinery work in the trenches and Bernard Moden would find himself working alongside him over twenty years later. Another interesting point to make here is the fact that a married woman (Louise) at this time was to be found working also in Roses helping the war effort by creating munitions. Before the War, a married woman working let alone working in a dirty smelly environment like a factory would be totally unheard of. But, in 1918 after four years of war against Germany, things were changing and women were an important and vital part of the workforce and helped Britain to win the war.

Sister Louise with her husband Bernard T. Hird.

Munition workers at Rose Bros, Gainsborough with sister Elsie in the front row seated on the extreme right.

The Family of Joseph Arthur and Agnes Moden at 68 Grey Street in the year of Bernard’s birth in 1918.

Joseph Arthur (dad) aged 45 – working in Rose Bros, Gainsborough

Agnes (mum) aged 44

Louise (sister) aged 25 married to Bernard. T. Hird. She was working in Rose Bros Munitions and living with her parents.

Frederick James (brother) aged 24 was in the army.

Elsie (sister) aged 21 was working in Rose Brothers Munitions.

William (brother) aged 18 was in the army.

Elizabeth May (sister) aged 16.

Joseph Arthur (brother) aged 13 worked at Marshall’s Trent Works.

Hilda (sister) aged 11, Ropery Road School.

Reginald (brother) aged 9, Ropery Road School.

Edith Mary (sister) aged 7, Ropery Road School.

Alice Ruby (sister) aged 3.

Albert Bernard Moden born on 23 February 1918 was the youngest child.

Listen to Bernard below talking about his own story in an oral history interview:

Albert Bernard Moden Oral history recording, 2015

As Bernard was growing up in Grey Street in Gainsborough, his family’s story continues. His brothers Fred and William (known as Bill) return home from War and Fred goes back to his job as moulder at Marshall’s. Bill finds a job for a short time at Roses however, he sees no prospects in Gainsborough and decides to contact his dad’s brother James Pedley Moden. His uncle Jim had emigrated to America and was well established. Uncle Jim replied and said there was work to be had over in America so he sent Bill the ten-pound fare. Elsie had a job working for Middleton’s of Morton as a housemaid. Bernard said ‘they must have liked Elsie, for when the Middleton’s died they left Elsie a small sum of money.’ In 1919 Elsie contacted Bill and sent her the ten-pound fare. Brother Fred took Elsie to Southampton, where she embarked on the S.S. Mauritania. She set sail for America in October 1919 when Bernard would have only been nearly two years old so he may not have remembered much about his sister. He said, ‘it was to be 41 years before we were to see Elsie again.’ On arrival in America Elsie took a job as a companion to a retired lady. She met John Morley who was working as a chauffeur at this address. She was later married to John by a Catholic priest at Boston, Massachusetts.

William (Bill) Moden (left) and Elsie Moden (right)

By 1921 five of the children had left home leaving six children including Bernard as the youngest child still living at home. Bernard’s dad Joseph Arthur Moden worked in the Iron foundries however, in 1921-22 the iron foundries were in a recession and he found himself on a three-day week. He moved on and found a job working on a farm on Blyton Road for a Mr Marriot. However, one day he went for a walk around Pilham and past Gilby Farm. John Ranby junior called him in and asked “are you looking for a job, Joe?” and he was offered a job with a house to live in as well. Upon accepting the job as a garth man who looked after stock, the role included wages at 30 shillings a week, free rent and milk, six fruit trees and a thirty stone pig per year.

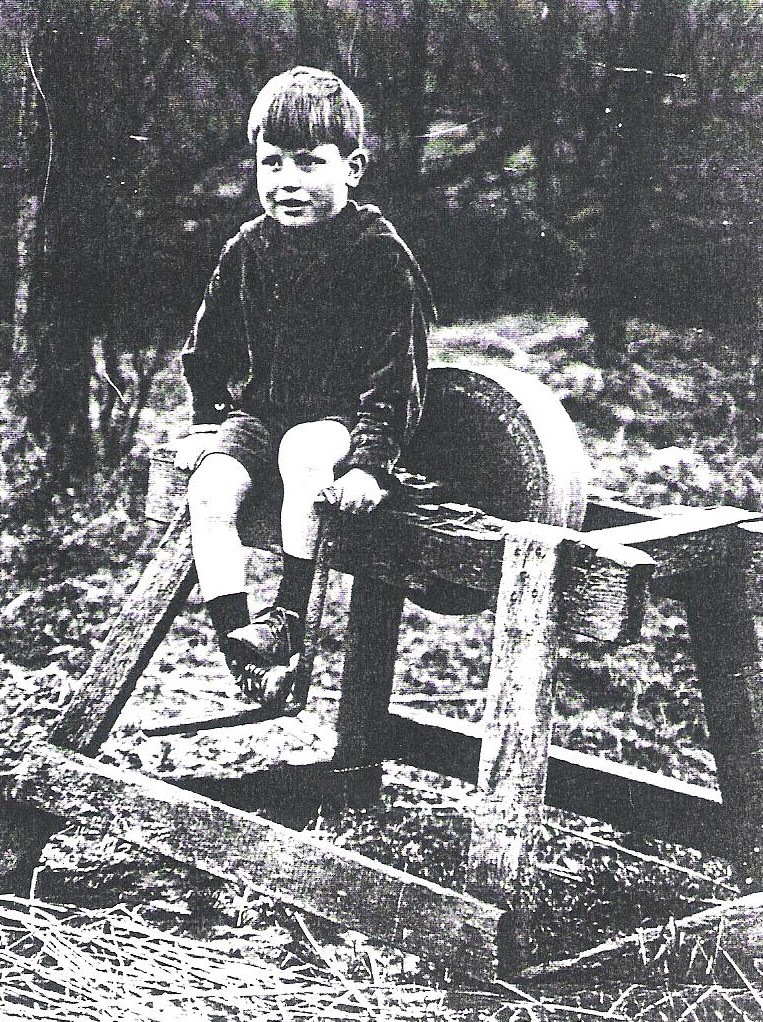

Albert Bernard Moden

1922 was a year of political upheaval within Irish affairs as this year saw the establishment of the Irish Free State in the South and West of the Island. George V was the reigning monarch at this time with David Lloyd George as the sitting Prime Minister. Times were hard in the years following the end of as it was known then ‘The Great War’ and jobs were in short supply. For Bernard’s dad to find a job with a house attached would have been an amazing achievement at that time. However, Bernard’s mother Agnes may have had different feelings as she was leaving No 68 Grey Street, Gainsborough. She would have been leaving a new house with a gas cooker, water toilet and, of course, the bay window which was a status symbol in those days. Upon arriving at Rose Cottage Farm, Aisby, ‘we found a very old stone farmhouse, set in the middle of a stackyard, surrounded by the usual farm buildings. Mother takes a look and starts to weep. She said “Oh Joe, what have you brought me to!” I think the place was in a bad state as far as the decoration was concerned. I know we didn’t live there long before mother papered right through.’

Joseph Arthur and Agnes Moden

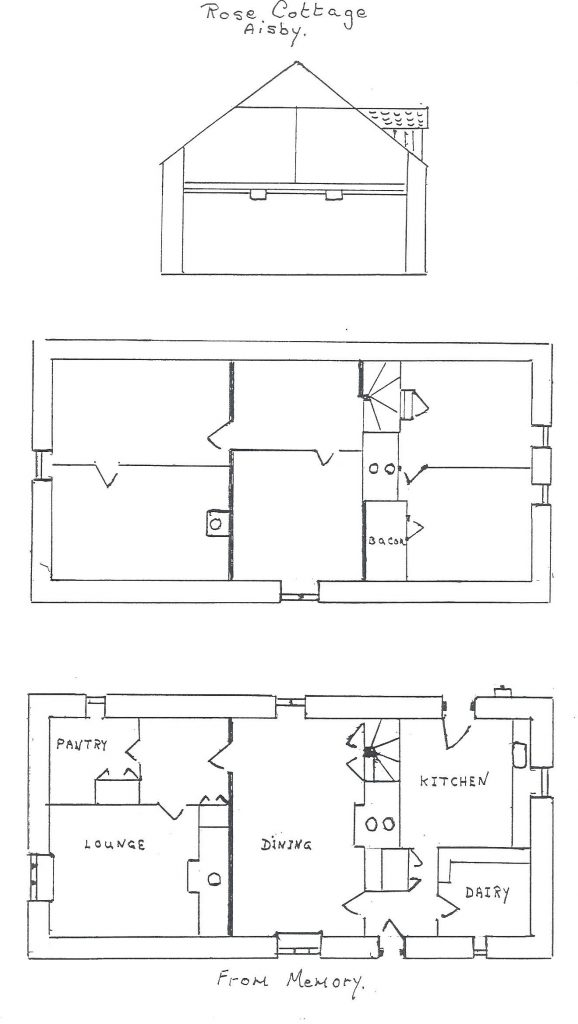

The family had moved to live in Rose Cottage in Aisby where there were only sixteen houses in total. Three of these were built of stone and they were the oldest buildings in the hamlet. Rose Cottage was one of these.

Outside the front door was a big round millstone which formed a doorstep. There was also a wooden archway with climbing roses. Through the front door was a passage, it was the heart of the house. One way lead to a dairy, with a brick gantry to salt pigs on and further down this passage was a kitchen with a fire range that never worked. Under the window was a yellow stone sink, to the side was a white wood worktop, with cupboards underneath. The backdoor was located in the kitchen with a wooden bar for a lock. Just outside the back door was the water pump and a paved area about three yards square, made up of small dark blue tiles.

From the front door the other way the passage led to the living room. It was a room with two Yorkshire light windows, the larger of the two having a window seat built into the wall. It had a beamed ceiling supporting a solid cement floor above. The cooking range was also in this room. ‘I couldn’t begin to tell you how much wood I collected for that fire, and when I wanted to put wood on the fire mother would say “I’ll make a fireman of you.” I didn’t care for that a lot. It was a large side oven, with a boiler on the other side for hot water, filled by hand from the pump outside.

In the living room was a door that led to the front room. Now, this door was a heavy oak door with three full-length vertical panels and a wrought iron ring to lift the latch, just like a chapel door. Through this door was another passage, it was very dark in there, for it had no windows. ‘My hair used to stand on end when I went in there, and sister Ruby was the same.’ At the end of the passage were two doors, one to the front room and the other to the pantry, with a four-door store cupboard. All the jars of jam were in here. Mother made lots of jam and there was an acre of orchard at Aisby so an easy supply. She made apple chutney, piccalilli, red cabbage and stored homemade wine in the bottom cupboard.

The front room had a three-light window, with a window seat. The fireplace had a low hearth fire, with a marble mantelpiece. The front room was the posh room; all the best furniture and pictures were in there. The piano and gramophone lived in the front room and Bernard’s sisters Ruby and Edith both played the piano.

The stairs were located in the living room. It was a winding flight, half-way up was a branch off to what used to be the servants quarters. There were two bedrooms and a bacon chamber. At the top of the main stairs were four more bedrooms, making six in all.

A typical day for Joseph Arthur Moden would be to get up at quarter to five in the morning. He would boil the kettle on a stick fire and then set off at 5.30am to walk to Gilby Farm about a mile across the fields. In winter-time when it was dark, dad would carry a paraffin lantern. On arrival, he would milk the cows and feed the stock and then return to Aisby carrying a can of milk that had been through the separator (the cream had been taken off). He would arrive back at 9am for his breakfast after which he would feed the stock at Aisby and do general farm work till dinner time. At 1.30pm he would make his second trip to Gilby to feed and milk the stock and he would get back home for about 6pm.

‘Mother worked very hard for the eleven years we stayed at Rose Cottage. She was the captain of the ship. Mother dealt with all the bills and correspondence. The letters she mostly wrote were to Grandparents Hawkins at Hillrow and letters to Bill and Elsie in America. When Bill and Elsie wrote home, there was always a few dollars in the envelope which mother used to take to the bank at Gainsborough to get changed. At the same time, if it was the season, she would take a stone of apples to Mr Mellis, the greengrocer. She got two shillings and sixpence, sometimes three shillings. If dad needed boots to work in, mother went to the town to buy them. In fact, mother bought all our clothes. Sometimes she would get a two-pound voucher from the Co-op which was two shillings a week for twenty weeks. That bought quite a bit. A boy’s suit was 18 shillings and sixpence and she washed, patched and darned.

Wash day was something at Aisby. The wash house was a stone building with a pantile roof with a 4ft opening, but no door. It had two fire coppers, we only used one. The other one had been used to steam pig potatoes. We had a mangle with wooden rollers, a washtub, dolly tub and dolly legs and there was no sink in the wash house. The floor had a good big slope and when you emptied the dirty water on the floor it ran down the slope, through a hole in the outside wall and into the council drain. Friday was baking day. The bread was made and put in a big yellow pippin in front of the fire to rise, it was a lovely smell when it came out of the side oven.’

Bernard started his school life at the nearby Corringham School. He recalls how he started to learn how to write on slates using a slate pencil with plasticine and bead frames and he was taught how to tell the time with cardboard clocks. ‘We learnt a lot through fear and little through joy. We soon accepted discipline. The cane wasn’t used much at Corringham. There was no need for it. If you did something wrong, they were on you like a ton of bricks. Miss Eyre, the infant teacher, would put a big kettle on the round stove at 11.30am and at midday, she made cocoa for the children who came from out of the village. We used to eat our packed sandwiches, washed down with free cocoa.’

‘When we moved up to the main school the headmaster was C. W. Frost, an ex-army man. He was strict on discipline but fair. Being a Church of England school, we always started with a hymn and then prayers. Robert Thornton, the vicar, came to teach us scripture once a week. The rest of the week we were taught by Mr Frost. Any event in the church calendar, such as Maundy Thursday, etc., the whole school would assemble and march off to church. We had been told previously, when the service was over we could go home but on no account must we run until we were well clear of the church.”

Corringham Church

I remember one Monday morning all the children were assembled in the main room. The headmaster called us all to attention and said “It’s come to my notice that some of you are not recognising the Rev. Thornton correctly. The boys must touch their caps and the girls must bow their heads. If you fail to do this, whether it be a boy or girl, I shall cane them,” We no doubt touched our caps after this, but we still called him “Long Bob.”

I remember one day, Edie and I were going to take dad’s dinner. Edie had got the basket with the food in it. She had got to the stackyard gate. I had to wait while my mother made the can of tea. Edie shouted come on. I dashed out of the back door, got halfway across the paved yard when I felt the paving tiles going down. I heard a splash, I screamed but kept on running. Mother looked out of the backdoor to find a hole in the yard where three of the blue paving tiles had fallen in. We had discovered the well!

Working Life

Bernard’s working life started on 1 April 1932, April Fool’s day. His brother Arthur got him an interview at the joinery works in Gainsborough called Trent Joinery Works, John George Cooling & Co. He went on Tuesday and was interviewed by Mr Whitehead, the works manager. After talking to me, he said “You should be sixteen before you go on a bench. I hear you want to be a joiner, so I’ll start you on a bench straight away.” He went on to say “If you start Friday you will get a full week’s wages as our week finishes on Thursday.”

The wages were 10/7d for a 46 ½ hour week. I used to leave Aisby about 6.40am and arrive at 7.30am start. I must have been mad, (we dare not be late). Mother packed sandwiches for the day. I got a blue enamel can to mash some tea in. Mother always had a cooked meal for me when I got home at 5.30pm. When I took home my first wages, mother gave me 1/6d to spend and to be saved for clothes, etc. and the rest for my keep.

‘I soon learnt the meaning of competition in the workshop. It was man against man. The joiner, if he didn’t compete, would lose his job. So he, in turn, put pressure on his apprentice. He knew there were a half a dozen others waiting at the gates to do his job. When the joiners left at 5pm, the apprentices worked two hours overtime, four nights a week. I asked Mr Whitehead if I could work overtime. He said “You know you have to be sixteen, but if you want to it will be alright.” So after tea, I always worked with a senior apprentice. I got 2/4d extra for my eight hours overtime. Mother agreed I could keep the extra to buy a new bike (mine was a wreck). I went to H. E. Cobb of Hickman Street and bought an Elswick Roadster for £4-19-6. I paid this off at 2/6d per week. I also bought a Lucas acetylene lamp (carbide gas) to see me home in the winter. No words can describe how proud I was of the bike.

When I started work the soup kitchens were in full swing. People queued up with their jugs and cans. Sir Hickman Bacon used to give rabbits from his estate. Edward, Prince of Wales, came to Gainsborough to open a social centre. The unemployed could go there and buy cheap wood to make stools, etc.

In the spring of 1933, the factory was closed for a week through lack of orders. I got a job for the week with a Corringham farmer, singling sugar beet, for wages of 2/6d per day.’

In the clip below, Bernard talks about his working life:

Albert Bernard Moden Oral history recording, 2015

In the 1930s the country was heading towards the events of WW2 and from Bernard’s memories we can see how the country was preparing for these situations. However, the general public’s feelings at that time can also be identified. For example, he remembered the newsreels at the cinema were showing the bombing in the Spanish Civil War and also German troops goose-stepping, but everybody laughed at them. He also recalled how when people saw German tanks on manoeuvres, people would say that half of them were cardboard. The Gainsborough News of 1937 advertised a searchlight demonstration on the Levellings. The News said it was to show the public our answer to enemy bombers. The editorial was saying they hoped there would be peace. The News advertised a series of air raid precaution lectures in 1937. Bernard also remembered a massive event in 1936, the abdication of Edward VIII being the talk of the workshop. The opinion, in the workshop, was, that he was a man of the people.

1938 was a big year for Bernard. He was working on the bay window bench, earning about 19/- per week. On January 31 the receiver was called in and what a bombshell, the men blamed management. Trade had started to pick up and more council houses were being built. The Works closed at the end of March and some of the men went away for work and others were on the dole.

‘A friend and I decided we would try the aerodrome. He was about a year younger than me. We cycled to Hemswell and went to the housing site office. The general foreman and joiner foreman were doing paperwork. We asked if there was work for a joiner. The joiner foreman said “Are you from that place that’s just closed down?” We said yes. Then he said “Then you don’t know anything about outside work.” He went on to ask what work we had done. We showed him our union cards to prove a point. He said “Very well, you can start on Monday. If you don’t fit in, you’re down the road.” He said “You will start at ten pence an hour.” The general foreman said “Give the lads a shilling an hour, they’re just starting out and they’ve their tools to buy.” So we started. It was the best thing that happened to me. I learnt how to get angles and bevels. The pressure wasn’t the same as the workshop, you had time to work things out. We were working from 8am to 6pm Monday to Friday and to 4pm on Saturday. We had two paid tea breaks, this was something new. I was cycling in from Blyton, but it was worth it, for I was taking home over £3 per week. After about two months the foreman said “If you keep your mouth shut, there’s tuppence an hour increase for you.” This was the first raise I’d had without having to ask for it. I remained at Hemswell till the first phase of houses finished (I returned later on the second phase).

Job number three was with Dorrington’s, a local building firm at Gainsborough. The company was run by a father and two sons. Son George was the joiner foreman who was also a director of Trinity football club. They were building the new Drill Hall on Ropery Road when I started. The work here had to be of a high standard. I also worked on the new houses on Ropery Road. These were selling for £450 or £475 if you had the bathroom tiled. When the Drill Hall was about finished George said “Will you stand-off for a fortnight, we’re short of work.” On Saturday morning I rode up to Kirton aerodrome. I saw the joiner foreman, he said start Monday. My job was on the married airmen’s houses. A young lad who worked at Dorrington’s called at our house and said “George Dorrington says you can start Monday.” I said “Tell him, thank you, but I’ve got another job.” After a few weeks cycling to Kirton I got a lift with an old joiner friend, in his Morris eight. After a while I heard that phase two houses had started at Hemswell, so I went back there. The standard at work here was much better than Kirton. It was about this time I got a motorbike for transport.

Bernard recalls his memories below of working for Rose Brothers during the War Years.

After the retreat from Dunkirk May 29, 1940, Hemswell aerodrome was on full alert for they feared an invasion. I received a green card from the Ministry of Labour to report to Rose Brothers of Gainsborough for an interview. I was asked if I’d done any milling or turning. I replied no. Mr Spivey said, “We’ll teach you.” I think it was June 1940 when I started. I had six months training in the Trent Works, then I moved over to the Levellings Works. The shop had just started. Some of the machines hadn’t been bolted down. They were brand new machines from America (lease lend). I went milling, the product was the Bofors gun.

By 1941 the shop was in full production. We were working twelve-hour shifts, six to six. It was this year I started to go out with Evelyn Falloon. We were on opposite shifts, so we met at weekends.

Evelyn Falloon

I didn’t have much spare time, there were Home Guard duties at Blyton and sometimes fire watching at Rose Brothers Works when your name came up on the rota. There was an aircraft observer on the roof at Roses, he recorded every aircraft that went over and in which direction it was flying. The firm ran a competition on the number of planes that flew over, it used to close at 4pm Saturday. Between 3pm and 4pm the observer would give a commentary on what was flying over and the number of planes for the week. If you hit on the number you got a prize. It was a shilling a go and the rest of the money went to the RAF Fund.

The wages weren’t as good as a Joiner’s. We worked piece work and drew our bonus once a month that seemed to even things out. We had a rate fixer called Mason. I’ve done battle with him a few times, he knew every trick in the trade. It was essential to get hold of good cutters. A man called Bill Lockwood of Morton took me under his wing. He always saw I had good cutters. We were both milling the same product.

In 1941 two bombs were dropped at Morton. One fell in the lake at Morton Hall, while the other plunged into the River Trent but neither detonated. A bomb disposal unit spent several months at the Hall attempting to remove the missile. The bomb was eventually abandoned due to the soft, boggy conditions and the depth of penetration. It was considered to be at a safe depth. The same view was taken regarding the bomb in the river.

A stick of bombs was dropped between Pilham and Bonsdale railway crossing. The bombs were all delayed-action type. A bomb disposal squad arrived to deal with them. They were billeted at Pilham Hall. In the evening they used the Victoria Club at Blyton where they got plenty of free beer. They also had to deal with two big bombs in the centre of Blyton. They were dropped at the back of Mr Humphrey’s farmyard.

A bomb was dropped on the main road at the bottom of Wharton Hill. A large crater was made on the road. Mr Wray’s farm opposite survived with only a small amount of damage.

In 1942, Bernard moved to live with his brother Fred and wife Gladys at 160 Trinity Street for about three months. He was there on 29 April 1942 when a Dornier bomber dropped a stick of bombs on the town centre. Seven people were hurt and six seriously injured. Four of the seven killed were soldiers when their mess, the Coffee Tavern, received a direct hit. There was extensive damage to property and Heaton Street ceased to exist. Market Street was a shambles with the Marquis of Granby being demolished and the Peacock Inn badly damaged. In all, 39 shops, the Town Hall, a row of dwellings, and the telephone exchange suffered widespread damage. Marshalls Engineers suffered blast damage to windows and the roof but they carried on production. ‘I think what surprised me most after the explosion was the number of people going up and down Trinity Street. When I went for the 6am day shift there were detours all over.’

Bernard married Evelyn at St Martin’s Church, Blyton, on Saturday 14 1942 and they moved into 3 Ebenezer Place, Morton, sited down a cul de sac, opposite the Church at Morton (shown in the image below). The opposite side was Belvoir Terrace, it was numbered the same (in 1954 the name Ebenezer was dropped and it became 5 Belvoir Terrace).

‘The House had three bedrooms and two good sized rooms downstairs. We had a very good pantry under the stairs and the house was lit by gas. We did our cooking with a coal-fired side oven, with a boiler at the other side for hot water. Outside we had a washhouse (laundry), coal store and toilet. The water tap was outside, sometimes this froze up in winter. We registered our ration books with Mr Lewis, the grocer, (next to the White Hart). He did his best for us but the rations were only in ounces. If he was in a very good mood you might get a shank end of bacon off the ration. The coop delivered the coal, this was also in short supply. The coalman was hounded, he had to leave everybody the same. Sometimes, he would come when it was dark and drop somebody an extra bag (if he had a backhander). Then every door would open, everybody wanted one, he used to say “It’s only slack!” We still wanted one. Mr Coulson was a smallholder of Cross Street, Morton. He came round with a horse and dray selling vegetables and homegrown fruit on a Saturday morning.’

The picture above shows in the centre Bernard Moden in 2008 on his 90th birthday, with Patricia Clarke (nee Plaskett) right and her husband Harold Clarke on the left. Bernard’s sister Hilda Moden married Jack Plaskett and Pat was their only daughter. Hilda and Jack lived on Belvoir Terrace in Morton in a different house for many years at the same time as Bernard and his family. One of his other brothers Reginald also lived in another house on the same street!

Bernard also remembered in 1942 on New Year’s Eve, ‘Evelyn and I were in the front room, it was early evening, a plane flew so low he nearly took the rooftops. I said, “He’s got to be in trouble.” The facts were searchlights were hunting for two Beaufighters on a training exercise over the town. There was a mid-air collision and one of the aircraft plunged into Noel Street in the north end of the town. Three houses were demolished and twenty others damaged by explosions and fire. The two crew were killed, along with a three-year-old girl who had been in one of the houses. The second Beaufighter was discovered the next morning, deep in the ground close to the General Cemetery. Both crew members were dead. When the air force rescue teams arrived there was a bit of confusion for they were also looking for a missing Wellington bomber, complete with bomb load, in our area. The Beaufighter unit was 409 (Nighthawk) squadron, Royal Canadian Air Force, based at Coleby Grange. They were carrying a new form of radar. I know that night we had a near miss.’

Photo of Bernard Moden, June 2004.

Bernard wrote about his memories in a book titled ‘The History of Joseph Arthur and Agnes Moden and their family as told by their son Albert Bernard Moden.’ Bernard died aged 99 in 2017.

Comments(3)

Heather Yates says

21st April 2020 at 9:37 amGemma – very interesting and loved the photos. The one of Belvoir Terrace brings back many childhood memories for me – I spent many happy hours playing and staying over in the house with Grandma and Grandad (Hilda and Jack). Also loved the photo of Bernard’s 90th birthday

Andrew Martin says

12th June 2020 at 11:22 pmHi Gemma, this is a wonderful piece – thank you. Bernard is one of my distant relatives and I’ve often had letters and emails from his son over the years. Reading this story about his life, and his memories of older relatives has really filled out those names on my family tree with much more character. Thank you.

Gemma Clarke says

14th June 2020 at 12:59 pmHi Andrew, thank you for your message, it’s fantastic to hear from you. I am so pleased you enjoyed reading my article and found out more about our family tree. If you need any more information, let me know. Thank you, Gemma

Recent posts

Events