Gainsborough is home to the stories of some very special women who were either born or grew up in the town of Gainsborough and worked really hard to develop and progress in their careers through many different eras. Women’s immense contribution to society has often been made invisible throughout history by a historic lack of social status and confinement to the home. However, women were often the key drivers in many a family business and a role that they were involved in would be to look after the money or accounts. The home was a central unit of production and women played a vital role in running farms, and in operating some trades and landed estates. For example, they brewed beer, handled the milk and butter, raised chickens and pigs, grew vegetables and fruit, spun flax and wool into thread, sewed and patched clothing, nursed the sick and much more.

The advent of Reformism during the 19th century opened new opportunities for reformers to address issues facing women and launched the feminist movement. The first organised movement for British women’s suffrage was the Langham Place Circle of the 1850s, led by Barbara Bodichon (née Leigh-Smith) and Bessie Rayner Parkes. They also campaigned for improved female rights in law, employment, education, and marriage.

Property owning women and widows had been allowed to vote in some local elections, but that ended in 1835. The Chartist Movement was a large-scale demand for suffrage but it meant manhood suffrage so the campaign for the vote for women was still key as the extract below shows in Gainsborough:

“Gainsborough’s first petition in favour of women’s suffrage was presented in May 1870. However, it was another 15 years before a suffrage meeting was held in the town, when, on 12 March 1885, Florence Balgarnie, Miss Tod, Mrs McCormick and Miss Taylour spoke in the Temperance Hall.

In the audience were Mrs Farmer and the Rev. William Winn Robinson, minister of the Unitarian Chapel in Beaumont Street and proprietor of a Middle Class School.

The following day the Rev. Winn Robinson took the chair when Florence Balgarnie addressed the workers at the Britannia Iron Works on the subject of women’s suffrage. Two years later, on the 18 January 1887, Miss Taylour returned to Gainsborough to give a lecture on the necessity of allowing women greater political and social equality with men. This meeting was chaired by a woman, Louisa Thompson. Miss Taylour was clearly popular in Gainsborough; she returned four months later, on 31 May to give another lecture, this time on ‘Women and Politics’, at a meeting of the Primitive Methodist Mutual Improvement Association.’

The extract above was taken from a book called The Women’s Suffrage Movement in Britain and Ireland, A Regional Survey by Elizabeth Crawford. The extract shows that people at that time in Gainsborough were supporting women discussing key issues and they were allowed opportunities to develop the support of the town’s people in the campaign for women’s suffrage and rights.

The women this article will focus on grew up in a time when they didn’t have the right to vote or many other key rights and persevering in a career was something often not heard of or seen as very different at that time. The first lady the article focuses on is a lady called Anne Mozley who was born on 17 September 1809 in Gainsborough. Anne’s career as a journalist began with her first literary writings in the 1830s. However, the first woman in Britain to earn a salary as a journalist was Eliza Linton who worked for The Morning Chronicle from 1848 to the end of the 1860s.

Anne Mozley was the sixth child of twelve children in a family that made notable contributions to publishing and journalism. Her parents Henry Mozley (1773 – 1845) and Jane Bramble (1783 – 1867) had at least the first eight of their children in Gainsborough and Anne was born in the town and was a younger sister of Thomas Mozley.

Anne Mozley (17 Sept 1809 – 27 June 1891)

The Mozley family had long had associations with publishing and printing within the town, Henry Mozley inheriting the business from his father John who had set up in business in the town as early as 1788 and is attributed with bringing the first printing press to the town. The family business was in the Market Place and was later taken over by Adam Stark and then Caldicott’s before becoming home to Woolworths in more recent years.

The family moved from Gainsborough to Derby in 1815 when her father moved the business there, where he later became a leading citizen and staunch supporter of the established Church. Anne’s early education although supplemented by the teachings of local masters with academic connections was a strict home education by a Governess with a routine that was rigorously imposed by her mother.

Anne’s outward life was exclusively that of a family and social one, a woman of artistic and intellectual interests belonging to a family in a provincial town that was part of the commercial elite. She was actively involved along with her sisters in visiting the poor and teaching young women’s classes and undertook ecclesiastical embroidery based on Pugin’s illustrations of medieval art. In 1832 her brother Thomas became the curate of Buckland and Anne became his housekeeper, she had been continually within reach of the intellectual life of Oxford through her brothers from the age of 16 and it was while with Thomas that she devoted herself to literary work. It was also at this time that Anne met the Newman’s two of whom were to become sisters in law and one a daily companion for many years while in Derby.

Anne Mozley’s literary work began when she selected and edited Passages from the Poets (1837), Church Poetry (1843), Days and Seasons (1845), and Poetry, Past and Present (1849) for the high Anglican publisher James Burns. In 1842 Burns established a children’s periodical called the Magazine for the Young for which Anne acted as editor, guiding among others the early literary efforts of Charlotte M. In 1846 she published a collection of historical narratives called Tales of Female Heroism, and her only identifiable work of fiction, The Captive Maiden: a Tale of the Third Century.

In 1847, after Newman’s conversion to Roman Catholicism, Anne Mozley’s brother James Bowling Mozley (1813–1878) became co-editor of the Christian Remembrancer, an organ of what remained of the Oxford Movement, and his sister contributed long review articles on general topics until it ceased publication in 1868. One of which on Thomas Grey was as sympathetic and fresh as any written on him. In 1859 she wrote four articles for the short-lived Bentley’s Quarterly Review (one of them the first review to identify the author of Adam Bede as a woman) this was long before her femininity was suspected, with precise and accurate reasons for her conclusions. This review delighted the popular author well known to the town, George Eliot, who asked for her next book (Mill on the Floss) to be sent to the same reviewer. Eliot said of the Adam Bede review “I think it is, on the whole, the best review we have seen”.

1861 saw Anne begin to contribute short essays to the Saturday Review (continuing as a contributor until 1877) and longer ones to Blackwood’s Magazine. All this work was unsigned and even the two volumes entitled Essays on Social Subjects: from the ‘Saturday Review’ (1865) do not identify the author. The bibliographic work is done with the records of major Victorian publishers since the 1960s has shown that Anne Mozley averaged two articles a year in Blackwood’s between 1865 and 1875, but her contributions to the Saturday Review and the Christian Remembrancer cannot be accurately identified.

Some of Anne Mozley’s identifiable journalism dealt with topical religious or political subjects like ‘English converts to Romanism’ (1866) or ‘Mr Mill on the subjection of women’ (1869), but the essays she chose to republish were in the tradition stretching from Addison and Steele through Lamb to Thackeray and discussed the minutiae of social life and the moral problems and obligations it raised, using a conventional man of the world persona and giving no hint of the author’s actual sex. Typical pieces reprinted from the Saturday Review dealt with ‘Cheerfulness’, ‘Commonplace people’, and ‘Social truth’, and from Blackwood’s with ‘Social hyperbole’, ‘Temper’, and ‘Schools of mind and manners’.

Anne stayed within the family until her mother’s death at which time she moved to Barrow-on-Trent with her sister, where they were recorded in the census as “annuitants” (someone who is receiving benefits from an annuity).

On the death of her brother James, Anne Mozley edited his papers, writing biographical introductions to his Letters (1885) and Essays Historical and Theological (1888). In 1884 Newman invited her to edit the letters of his Anglican period. Her nephew Francis Mozley wrote in a ‘Memoir’ included in her Essays from ‘Blackwood’ (published posthumously in 1892) that she had accepted the invitation because she felt that ‘no one besides was left having such freedom of position and such personal recollection of the events that happened fifty or sixty years before’. Her edition was published in 1891. In 1889 her sight was failing and she returned to Derby to live with her surviving sisters and a niece. Despite her eyesight, she enjoyed good health, but a cold in 1891 rapidly developed into serious illness. Anne Mozley died within a few days at St Werburgh, Derby, on 27 June 1891.

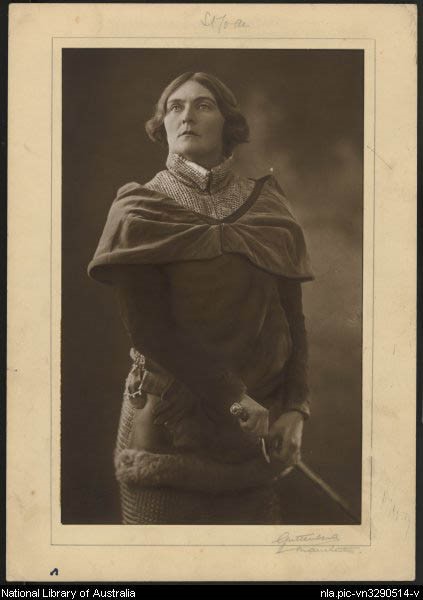

Dame Agnes Sybil Thorndike CH DBE (24 October 1882 – 9 June 1976)

British stage actor Sybil Thorndike (1882-1976) was one of the leading figures in British theatre during the first half of the 20th century. She made her stage debut in a regional company production of “The Merry Wives of Windsor” in 1904, and achieved her greatest success in the title role of “Saint Joan”, a play written for her by George Bernard Shaw in 1924. Thorndike achieved an amazing career but when she was born on 24 October 1882 women in the theatre were only gaining ground slowly but surely. There were female playwrights, females acting on stage, plays that gave female characters a prominent role, and also, many females in the theatre audience. “Women helped change the dynamic of theatre in the second half of the 19th century and were directly responsible for the rise in its popularity.” While men still had a larger presence in the theatre world, females did some pretty interesting things. One notable example was Victorian-era Burlesque theatre, during the 19th century in both England and America. Women were often featured in masculine roles. Playing crazy characters and reversing gender norms definitely did not create a respectable reputation for these women but this was an important step for women because it allowed women to rebelliously break free of many restrictive social expectations. More and more types of theatre emerged as time went on. And as theatre expanded in a variety of different directions, women’s importance in the theatre was also expanded.

Focusing on Agnes Sybil Thorndike and her story, she was born in Gainsborough, Lincolnshire to Arthur Thorndike and Agnes Macdonald. Her father was a Canon of Rochester Cathedral. She was educated at The Rochester Grammar School for Girls, and first trained as a classical pianist, making weekly visits to London for music lessons at the Guildhall School of Music and Drama.

She gave her first public performance as a pianist in Rochester at the age of 11. Compelled by painful hand cramps she had to abandon her musical aspirations. Thorndike quickly transferred her creative expression to the theatre at the suggestion of her younger brother, Russell Thorndike. At the age of 21, she was offered her first professional contract: a tour of the United States with the actor-manager Ben Greet’s company. She made her first stage appearance in Greet’s 1904 production of Shakespeare’s The Merry Wives of Windsor. Thorndike and her brother travelled throughout the United States with this group, and she gained extensive stage experience during the tour, playing more than 100 minor roles and serving as understudy to several leading roles. She remained with Greet’s company until 1907, giving performances as Ceres in The Tempest, Viola in Twelfth Night, Helena in All’s Well That Ends Well, and advancing from Lucianus to Gertrude to Ophelia in Hamlet. In 1908 Sybil was spotted by the playwright George Bernard Shaw when she understudied the leading role of Candida in a tour directed by Shaw himself. There she also met her future husband, Lewis Casson. They were married in December 1908 and had four children – John (1909), Christopher (1912), Mary (1914) and Ann (1915).

In addition to their interests in theatre and music, Thorndike and Casson shared concern for leftist social and political causes. They had four children and remained married until Casson’s death at age 93 in 1969. As part of Horniman’s company at Manchester’s Gaiety Theatre in 1908 and 1909, Thorndike undertook such roles as Mrs. Barthwick in The Silver Box by John Galsworthy, Artemis in Gilbert Murray’s adaptation of Hippolytus by Euripides, Thora in The Feud by Edward Garnett, and Bettina in The Vale of Content by German dramatist Hermann Sudermann. For a time she joined Charles Frohmann’s company in London and appeared in various roles, including Columbine in The Marriage of Columbine by Harold Chapin at the Court Theatre, and Winifred in The Sentimentalists by George Meredith, and Emma Huxtable in The Madras House by Harley Granville Barker, both in 1910 productions at the Duke of York’s Theatre.

Thorndike also made her Broadway debut at the Empire Theatre in 1910, playing the role of Emily Chapman in the comedy Smith by Somerset Maugham. Touring U.S. theatres in this part throughout 1911, she returned to England and rejoined Horniman’s company, going on to perform such roles as Beatrice Farrar in Stanley Houghton’s sensational Hindle Wakes at London’s Aldwych Theatre in 1912, and Ann Wellwyn in John Galsworthy’s The Pigeon and Lady Philox in Harold Chapin’s Elaine, both at the nearby Court Theatre. Renewed productions at Manchester’s Gaiety Theatre included Portia in Shakespeare’s Julius Caesar, Privacy in Harley Granville Barker and Laurence Housman’s Prunella, and Hester Dunnybrig in Eden Philpott’s The Shadow.

In 1912 Thorndike originated the role of Jane Clegg in St. John Ervine’s realistic drama of the same name. Thorndike’s portrayal of Jane Clegg, a wife coming to terms with her husband’s infidelity and the utter failure of their marriage, became among the best-known roles of her career; she recreated it for London revivals in 1913, 1914, 1922, and 1929, toured internationally with travelling productions of the play, and performed the role for the last time in January of 1967. According to a London Times reviewer discussing Thorndike’s dual performance of Jane Clegg and Medea at the Wyndham Theatre in 1929, “It is the peculiar power of Miss Thorndike’s acting that it can draw to a character just as much sympathy as it deserves and no more. In the quietly felt tragedy of the commercial traveller’s wife, no less than in the dreadful and insistent Medean clamour of revenge, this power of shedding clear, unsentimental light on the complexities of character was equally effective.”

In 1914 Thorndike joined Lilian Baylis’s Shakespeare company housed at the Old Vic in London. There she distinguished herself in a number of roles, including Lady Macbeth, and became a favourite of audiences. During this time, whilst many male actors – including Lewis Casson – were serving in the British Army during World War I, Thorndike added a number of male roles to her resumé. Among these were performances as Prince Hal in Henry IV, Puck in A Midsummer Night’s Dream, the Fool in King Lear, and Ferdinand in The Tempest.

In the postwar years, Thorndike was a fixture of the London theatre season, and appeared in numerous successful productions, including comedies, tragedies, Grand Guignol, modern works, and stage classics. Commenting on the quality of her voice in a 1922 performance of La Tosca at the Coliseum, a reviewer in the London Times wrote that Thorndike’s “wonderful voice could be heard in every corner of the vast theatre, and yet she never seemed to be raising it at all unduly.… The whole performance was a single triumph for one of our most capable actresses. She was recalled time and again before the curtain.” Most notable among her roles of this period are her interpretations of Hecuba in The Trojan Women and in the title role of Medea, both works adapted from the Greek by Gilbert Murray. So successful was Thorndike at portraying these characters that she participated in revivals of these productions until the mid-1950s. Of Thorndike’s performance as Medea at London’s New Theatre in the fall of 1922, a London Times, reviewer faulted Thorndike’s vocal style, but concluded that “her performance never falls short of its full tragic effect, and is remarkable, not only for its force but for the intellectual insight it exhibits.” In addition to these roles, Thorndike made her film debut in 1921 and assumed management, with Casson, of the New Theatre, London, in 1922.

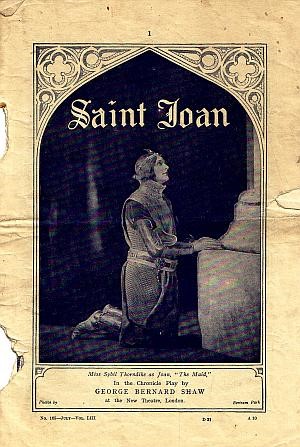

A resurgence of interest in 15th-century figure Joan of Arc, the French national heroine who led a troop of soldiers in the last phase of the Hundred Years’ War, took place in the early 1920s following Joan’s canonization as a saint of the Roman Catholic Church. Thorndike originated the role of Joan in Shaw’s Saint Joan, which debuted at the New Theatre in London in 1924 and ran for 244 performances. The part, which was written specifically for the actress by the 67-year-old Shaw, brought her critical acclaim and became a popular favourite, and Thorndike was called upon to revive her interpretation in revivals at London theatres in 1925, 1926, 1931, and 1941. She also performed the role of Joan before appreciative French audiences at the Théâtre des Champs-Elysées in Paris in 1927, as well as on international touring productions to South Africa in 1928-29, to Australia and New Zealand in 1932, and to the Far East in 1954.

Throughout the ensuing decades, Thorndike acted in a wide selection of dramas and comedies both classical and modern. In addition to Shakespearean and Greek heroines, she portrayed leading roles in a number of works by Shaw, Henrik Ibsen, Noel Coward, Emlyn Williams, and Clemence Dane. Thorndike made her television debut in May of 1939 as the Widow Cagle in Lula Vollmer’s Sun Up, a redemption drama set among the mountain folk of North Carolina in 1917. On the occasion of her 70th birthday in 1952, a drama critic writing in the London Times noted that “As the years have passed there has been no decline in Dame Sybil’s art: indeed, it has deepened in feeling and technical assurance, delighted in widened virtuosity.”

Both Sybil and Lewis were active members of the Labour Party and held strong left-wing views. Even when the 1926 General Strike stopped the first run of Saint Joan, they both still supported the strikers. Nonetheless, she was made a Dame Commander of the British Empire in 1931. As a pacifist, Sybil was a member of the Peace Pledge Union and gave readings for its benefit. During World War II, Dame Sybil and her husband toured in Shakespearean productions on behalf of the Council For the Encouragement of the Arts, before joining Laurence Olivier and Ralph Richardson in the Old Vic season at the New Theatre in 1944.

Not influenced by such passing fashions in acting style, Thorndike remained true to her heritage and was applauded for doing so. In a 1953 Green Room Rag performance, Thorndike and Casson re-created the scene in Henry VIII in which Queen Katherine receives the two cardinals. According to a London Times reviewer, Thorndike’s “Queen Katherine is less an interpretation of her own than a true illumination of the text. She adds nothing to the character, as a clever actress of the second rank might do; she is content merely to reveal everything that is there. But it is in simple revelations such as this that the characters of the drama assume for the moment a reality greater than the people about one and that actors and actresses declare their own greatness.”

Shakespeare’s Henry VIII was chosen in 1954 for a special performance in honour of Thorndike’s Golden Jubilee. Fifty years to the day of her first stage appearance, Thorndike, along with fellow actors Casson, Laurence Olivier, John Gielgud, Ralph Richardson, and Robert Donat, performed a version of the play for the BBC Home Service. In addition, Thorndike was presented with a commemorative statuette of herself as Joan of Arc.

She continued to have success in such plays as Waters of the Moon. She also undertook tours of Australia and South Africa, Thorndike and Casson created new roles in Eighty in the Shade, a play written specifically for them by Clemence Dane that premiered at the Globe Theatre in 1959. She continued working through the 1960s, appearing as Lotta Bainbridge in Waiting in the Wings by Noel Coward at the Duke of York’s Theatre, as Marina in Chekhov’s Uncle Vanya at the Chichester Festival Theatre, as Abby Brewster in Arsenic and Old Lace by Joseph Kesselring at the London’s Vaudeville Theatre, and as Mrs. Bramson in a touring production of Night Must Fall by Emlyn Williams, among other roles. Her last stage performance was at The Thorndike Theatre in Leatherhead, Surrey, in There Was an Old Woman in 1969, the year Sir Lewis Casson died.

In 1969 Her Royal Highness Princess Margaret and Lord Snowdon attended the dedication of the Thorndike Theatre in Leatherhead, outside of London. (The Thorndike has since closed and reopened under new management as The Theatre.) Thorndike’s farewell stage appearance was in the Thorndike Theatre’s first production, John Graham’s There Was an Old Woman, in which a homeless old woman recalls her life from her optimistic days as an attractive young newlywed through the long struggle of her widowhood and eventual institutionalization. Her final appearance was in a TV drama The Great Inimitable Mr Dickens, with Anthony Hopkins in 1970.

The same year she was created a Companion of Honour. Thorndike, who had been made a Dame of the British Empire in 1931, awarded an honorary degree from Manchester University in 1922, and an honorary D.Litt from Oxford University in 1966, died following a heart attack at her home in south-central London in June of 1976. Dame Sibyl’s ashes are buried in Westminster Abbey. When it opened in March 1974, the re-routed A631 dual-carriageway southern relief road constructed by Lindsey County Council in her birthplace of Gainsborough was named Thorndike Way.

Beatrice Daisy Girdlestone born in Norfolk in 1881 moved to Gainsborough with her family when she was 15 years old in 1908 and was the daughter of a flour miller’s roller man. Daisy was a professional photographer and dance teacher with her own school and was well known across Gainsborough.

Interestingly, women have been an active part of photography since its inception. While not credited with the invention of photography, women have played significant roles working alongside the pioneers, often printing for their husbands, and taking photographs themselves. Joseph Niépce, the inventor of photography, talked through his experiments in letters to his sister-in-law. Constance Talbot (1811-1880), the wife of photography pioneer Henry Fox Talbot, and Anna Atkins (1799-1871), an English botanist and friend of the Talbots, were the first female photographers. They were taking photographs alongside Talbot and his peers as they developed and advanced the earliest photographic methods.

Queen Victoria was a champion of the photographic arts. In addition to granting her patronage to what became The Royal Photographic Society, Queen Victoria started the practice of putting visiting cards in albums. As the practice caught on among aristocratic women, photograph albums became a show of status, spreading the demand for and appreciation of photographic culture. By the 1880s, Kodak had recognized the increasing participation of women in photography and launched a marketing campaign with the Kodak Girl. About the same time, women photographers and journalists began actively advancing photography as a suitable profession for women. British and American censuses show that by 1900, there were more than 7000 professional women photographers. Women made up almost 20 per cent of the profession at a time when it was unusual for women to even have a profession.

Daisy Girdlestone’s Dance School

Daisy staged her first pantomime in 1913 and continued this tradition every year except during the war years. In 1952, the Merry Madcaps troupe took to the stage to perform Babes in the Wood and that was her thirtieth and last production for ‘the star producer who devoted almost 40 years of her life to the town’s theatre.’ Miss Girdlestone’s long and distinguished pantomime career ended when she collapsed during rehearsals in 1953. She died aged 70 years at John Coupland Hospital on 25 January 1953. The script of her New Year Pantomine, ‘Goody Two Shoes’ was buried along with her in Gainsborough’s General Cemetery.

As worldwide events have occurred throughout history women have always taken on important roles and were essential workers from 1914 to 1918 supporting the War effort. Women were involved in many different ways from working in the industry in munition factories such as Marshall’s and Roses of Gainsborough to working on the land as well as other vital work and these experiences changed women’s lives.

By the time Miss Peart was born in October 1919, Women over the age of 30, with certain property qualifications, were granted the right to vote in Britain just a year earlier and in that same year, a lady called Constance Markievicz became the first woman elected to parliament.

Phyllis Peart is known for her hard work and perseverance of her career as a nurse, midwife and health visitor. However, it is worth mentioning here that if it wasn’t for the work of nurses like Phyllis, it may still have been difficult for women to work in this profession. Florence Nightingale demonstrated the necessity for professional nursing in modern warfare and set up an educational system that tracked women into that field in the second half of the nineteenth century. Nursing by 1900 was a highly attractive field for middle-class women.

Medicine was very well organized by men, and posed an almost insurmountable challenge for women, with the most systematic resistance by the physicians, and the fewest women breaking through. One route to entry was to go to the United States where there were suitable schools for women as early as 1850. Britain was the last major country to train women physicians, so 80 to 90% of the British women went to America for their medical degrees. Edinburgh University admitted a few women in 1869, then reversed itself in 1873, leaving a strong negative reaction among British medical educators. The first separate school for women physicians opened in London in 1874 to a handful of students. In 1877, the King and Queen’s College of Physicians in Ireland became the first institution to take advantage of the Enabling Act of 1876 and admit women to take their medical licences. In all cases, co-education had to wait until the First World War.

Phyllis grew up in Gainsborough after the First World War and attended local schools. After leaving school in Gainsborough she began her career with clerical work in Gainsborough and Lincoln. However, during the Second World War Phyllis started her general nursing training at Scunthorpe Hospital. When she started her nursing training, she was just put into uniform and then placed straight onto a hospital ward.

Photo courtesy of Phyllis Peart’s book Nursing Midwifery & Me (2015).

‘We had no knowledge of nursing and certainly had to learn very quickly. It was in the early years of the War, well before there was a National Health Service. There was no initial training period, I was just put straight on the ward to help. Long stay patients were a fount of wisdom, and even the short-stay patients knew more about nursing than I did then. One of the first things I was given to do was to give bedpans out and it was in a women’s ward. We soon started attending lectures. Some lectures were given by Sister Tutor, and some by members of the medical staff. We were given practical demonstrations of nursing techniques and tried our hand at various things. We faced the prospect of not only nursing on the wards but also in the Outpatients Department. There we would be helping in different clinics, and be involved in casualties. Then there was the Theatre, where there were various techniques to learn, so we could help with the different operations, which took place.’

The Hospital at which Phyllis trained was a voluntary hospital meaning it was supported by public funds. Workmen gave so much each week and people raised money in various ways and often bequests were made to the hospital. Phyllis thought that this was not a bad thing as it made everyone aware of their responsibilities to the community. Phyllis left this hospital to take further training before the National Health Service became law.

Phyllis decided to train as a midwife in Sheffield during 1946 and 1947 just after the end of World War Two, and she recalled how everyone who could at that time were having a baby so it was a busy time for her in the hospital. Phyllis passed her examinations for Part One Midwifery and applied to a Queen’s Nursing Home to take Part Two Midwifery training.

Photo courtesy of Phyllis Peart’s book Nursing Midwifery & Me (2015).

‘The first delivery that I was taken to, by a training midwife, was to deliver a mother of her eighth child. This home had no luxuries. The father never seemed to work. His wife, however, seemed to think very highly of him. The eldest child, who was about eleven years old at the time, was very competent in getting us what we needed. She really showed more efficiency than some adults. It was in some ways sad that she was so old for her age, but she had never known anything different. All the other children were girls, and the parents did really long for a boy. The labour took its usual course, and the baby was born. IT WAS A BOY!! There was great rejoicing. I went to care for the mother and baby every day, and I was very well received indeed!’

Phyllis explains that before the National Health Service began, the Queens Homes were funded locally so when mothers had their babies they were charged for the confinement, and, this is what Phyllis did not like, they had to collect the money. If they had to organise the delivery, and no doctor attended, the fee was twenty-five shillings. If however, a doctor was booked, the fee for the midwife was less, fifteen shillings.

Phyllis passed her Part Two Examination and became a State Certified Midwife. She then decided to complete her Queen’s District Training. She did four months in the City of Sheffield where she had completed her First Part Midwifery Training and worked for two months where she had taken the Second Part of her Midwifery Training. After passing the Queens examination, Phyllis stayed at the Home for some time doing general district work and some midwifery work.

Phyllis was now a State Registered Nurse, State Certified Midwife and a Queen’s Nurse and commenced a period of working within the community. In 1948 the National Health Act of 1946 became law and its implications were far-reaching. More people were able to access Health Care and as health services improved in the knowledge of better treatments of different conditions helped more babies to survive.

After many years of hard work Phyllis then decided to train as a health visitor and applied to University where health visitor training was offered. She obtained a bursary from the County Health Authority attached to Nottingham University however, this meant that if she passed the examination, and became a health visitor, she would have to serve with the Authority for at least two years before being free to move on. Health Visiting began in Manchester in the year 1862, when it formed part of the activities of the Manchester & Salford Ladies’ Health Society. At first, the work was limited due to the circulation of tracts on health subjects, but, when it was found that these made little impression, “visitors” were engaged to give simple home instructions to mothers in domestic hygiene. These visitors also distributed soap and disinfecting powder.

As the work of these health visitors developed the importance of attacking infant mortality became more widely recognised, and in 1890, by arrangement between the Society and the City of Manchester, their work was brought under the direction of the Medical Officer of Health. The Local Authority paid a substantial proportion of the visitors’ salaries. By 1892 Buckinghamshire County Council appointed three “Lady Missioners” to give home instruction in child welfare. This step was taken on the initiative of Florence Nightingale, who recommended also that the Technical Committee of the Council should arrange a course of instruction followed by an examination. The number of health visitors appointed by local authorities was considerably increased after the passing of the Notification of Birth Acts in 1907 and 1915.

Until 1919 there was no officially prescribed course of training for health visitors, nor was any standard in proficiency formulated. In that year, however, the newly established Ministry of Health, in co-operation with the Board of Education, laid down certain conditions governing the training and appointment of health visitors. In 1925 these were made more comprehensive and exacting. In 1949 the syllabus was, with the approval of the Ministry of Health, again revised and broadened to meet the new demands made upon the health visitor.

After this, to be accepted for health visitor training, students had to be State Registered Nurses, and have at least passed their Part 1 Midwifery examination. The duties of a health visitor included being involved in antenatal care, the care of babies, pre-school children and school children as well as helping Tuberculosis patients and looking after the elderly.

Phyllis worked in Retford for some years, before finally coming back to Gainsborough where she worked until she retired. Phyllis wrote two books about her life story which are available in the Heritage Centre shop and copies can be purchased when the Centre re-opens. The first focuses on her career titled, ‘Nursing, Midwifery and Me’ and the other is called ‘Reminiscences’ focusing on her life growing up in the town of Gainsborough.

Phyllis Peart is shown with a couple of other members of the Old Girls Association (she is on the far left of the picture).

Constance Kirk was another important Gainsborough character and the only child of William and Ellen Kirk. Her father William was an accountant for the Gainsborough Urban District Council. Connie started her working life at Edlington’s in Carr Lane. Her father set Connie up with a tobacconist shop in 7 Market Place and her mother, Ellen, helped her to run the business.

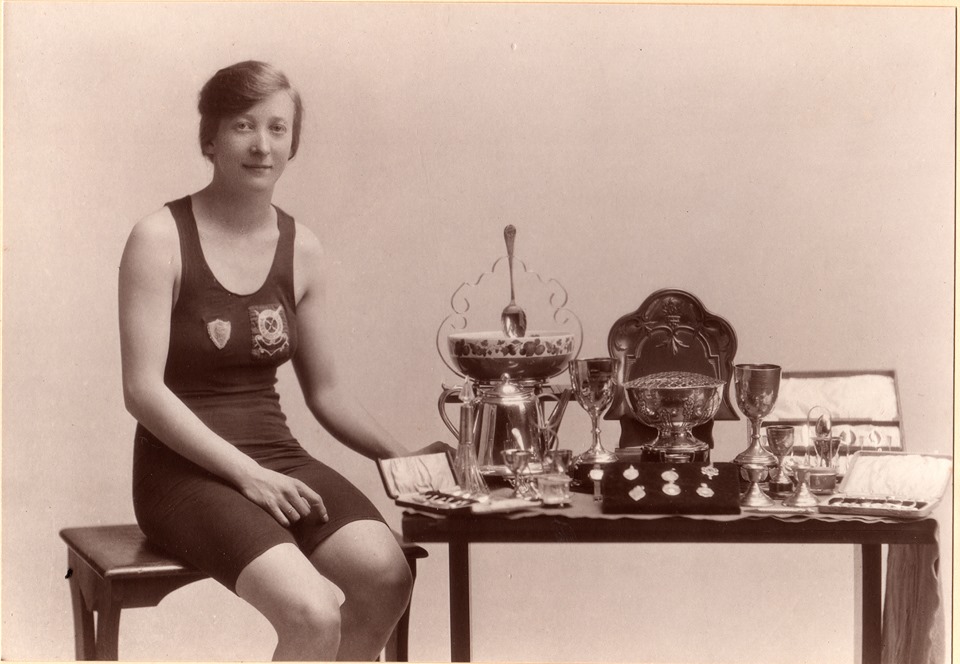

Photo courtesy of Paul Kemp

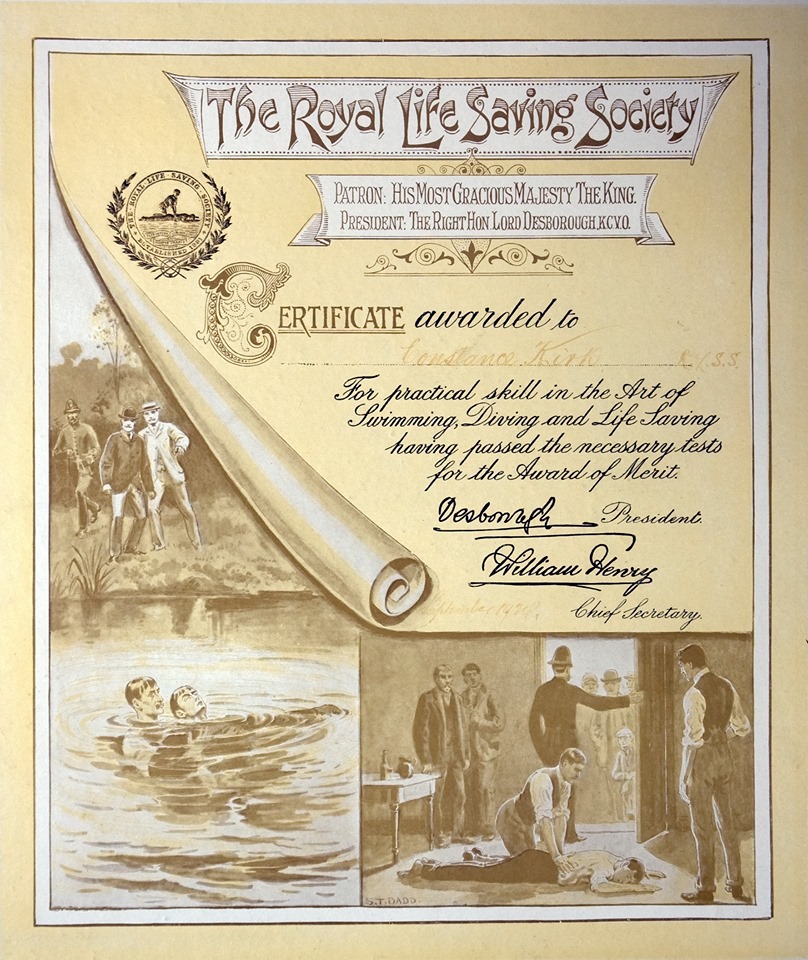

A lover of music Connie was a very able pianist and she had a grand piano where she lived in Gainas Avenue. She sang with the Gainsborough Musical Society for a long time and was for some years a member of the Amateur Operatic Society. Connie was an enthusiastic swimmer and she used to be taken to the Lea Road baths in her pram by her parents who were also keen swimmers. A prolific cup winner Connie won the Ladies Senior Championship several times before winning it outright, twice she was second in the Lincolnshire Ladies Championship of 220 yards and had taken many examinations in life-saving.

Photos courtesy of Paul Kemp

When the Nottingham Evening News organised an open swimming event in the Trent Connie was one of the entrants. The competitors one of whom was 70 years old, took off from moored barges and at the Trent Bridge end of the course a marquee was erected on the bank and a band played – no doubt a welcoming tune at the end of a long cold swim! A report titled Gainsborough Girl’s Splendid Effort at Nottingham in the big swim in the Trent said that, ‘The promoters gave a medal to all who completed the course, and Miss C. Kirk, also of the Gainsborough Ladies’ Club, was successful in obtaining one of these, and swam very well indeed, being well amongst the leaders for most of the distance.’

The Gainsborough News reported on Friday, September 17, 1926 a story of a remarkable swimming record, details below:

Miss C. Kirk, daughter of Mr. Wm. Kirk, of Market Place, Gainsborough, with the numerous trophies she has secured in swimming contests. At the Swimming Sports in connection with the Gainsborough Ladies’ Swimming Club on Saturday, Miss Kirk retained the Senior Championship of Gainsborough for the fifth year in succession. Miss Kirk has twice been second in the Lincolnshire 220 yards’ championship, in 1925 and 1926. She was the winner of the Rose Bowl for the 120 yards scratch race at Gainsborough in 1924 and 1925, but she lost this race this year. She was twice second for the Junior Championship, in 1913 and 1914, and last year she won the Life Saving Award of Merit. Miss Kirk has won one senior championship trophy outright and she will be able to claim another next year if she is again successful, as she has twice held the new trophy. These are only some of the outstanding performances of Miss Kirk’s remarkably fine record.

In an interview with the Gainsborough News in 1951, Connie explained how: ‘Fashions in smoking have changed like everything else and nearly all young men have forsaken the pipe for cigarettes now.’ Connie’s shop in Gainsborough and her own personality was very popular with many people and as a local woman, she showed people that you could own and run your own shop.

However, Connie closed her business on 30 July 1960 after 36 years. In an article dated July 1960 it states that ‘The shop has been run single-handed by Miss Connie Kirk, since 1924, when her father, Mr. W. Kirk, set her up in business. Until a few years ago, Miss Kirk and her father and late mother lived “on the premises” in the flat above the shop but now reside in Gainas Avenue. After leaving school, Miss Kirk worked in an office for a time, but she told a “News” reporter she had enjoyed running her own business and meeting people. In her younger days, Miss Kirk was a strong swimmer and was closely connected with Gainsborough Swimming Club. She won many cups and trophies in galas and has even swum in the River Trent. Miss Kirk is looking forward to retirement and intends to go about as much as possible and keep on her hobbies of music and gardening. She has been a member of Gainsborough Musical Society for many years.’

In an article by Dawn Bond, ‘Nine charities are to benefit to the tune of almost £98,000 in the will of a former Gainsborough tobacconist. Constance Kirk, who died in March after a short illness in St George’s Hospital Lincoln, also left £250 to the League of Friends of John Coupland Hospital in Gainsborough. The 90-year-old left most of her money to charities for the blind in memory of her blind grandfather. Miss Kirk, who lived in Gainas Avenue. Before opening her tobacconist’s shop in Gainsborough’s Market Street, she worked as a secretary for Edlington’s agricultural engineers in Carr Lane. Miss Kirk was a keen swimmer and diver, belonging to Gainsborough Swimming Club. But music was the greatest love of her life. She played the piano and sang soprano with the town’s Choral Society and its Operatic Society. She was a regular worshipper at All Saints Parish Church in the town and was widely travelled, including Norway, Malta and Egypt in her overseas journeys. Marjorie Burton of Edward Road, Gainsborough worked for Miss Kirk at her home for 25 years. Miss Burton said: “Connie was never lonely. She was always friendly and would talk to anybody. There was no uppishness about her. She was a regular churchgoer, a good swimmer and she was a very good singer.’

Photos courtesy of Paul Kemp

Women’s rights and attitudes to women in the workplace or in certain roles such as theatre, journalism, photography, nursing and retail developed and improved and this was due to the hard work and perseverance of women like the ladies seen in this article. However, changes still needed to be made as it was still difficult for women to access some career roles. 1970 sees the introduction of the Equal Pay Act and as late as 1986, maternity pay was introduced. The next three ladies in this article grew up in times when women had already paved the way in many careers but many changes were yet to happen to help women advance on their career paths.

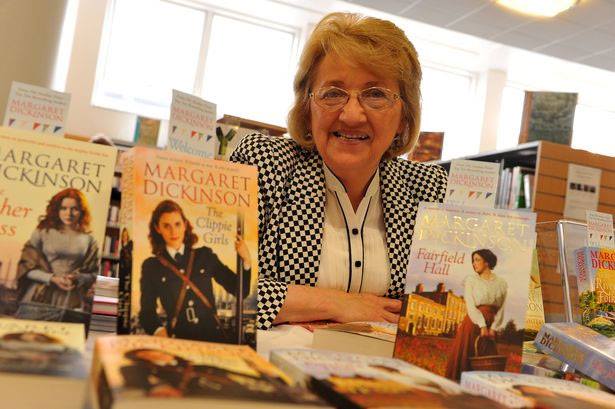

Margaret Dickinson was born in Gainsborough at the North Marsh Road maternity home, Lincolnshire. Margaret literally entered the world with a bang, her birth date being 30 April 1942, the night following the German Air Raid that destroyed a large part of Market Street. Her father was born in Beckingham, just across the Trent from the Town and her mother was born at Morton in 1900. Both Margaret’s maternal grandparents were teachers within the town; her grandfather was a visiting art master at the secondary schools and Headmaster of the Evening Institute, the classrooms of which were above the Marshall’s Works. Both her mother and grandmother taught embroidery within this establishment. She has spent most of her life in the county, moving to the East Coast from Nottinghamshire at the age of seven.

Margaret Dickinson

She began writing at the age of fourteen with the ambition to be in print and her first novel was published in 1968. Seven others followed this between 1969 and 1984 but then, because of family commitments, Margaret was unable to write for seven years. In 1991, encouraged by her husband to begin writing again, Margaret had that little piece of luck that everyone needs – she found a wonderful literary agent, Darley Anderson, who advised her to write a regional saga with a strong woman as the central character.

In 1993 Pan Macmillan offered a two-book contract for Plough the Furrow, the first in the Fleethaven Trilogy, and its sequel, Sow the Seed, which was published in 1994 and 1995 respectively. It seemed as if Margaret had found her niche; writing romantic fiction and bringing to life her love of the sea, the Lincolnshire landscape and its people. Reap the Harvest, published in 1996, completed the trilogy. Church Farm Museum at Skegness – a “living” museum – was the model for Brumbys’ Farm and the setting was Gibraltar Point.

In 1997 The Miller’s Daughter, inspired by the windmill at Burgh-le-Marsh, near Skegness, was published and in the following year, Chaff Upon the Wind took the Manor House at Alford as the setting for the characters in the story. Grimsby was the inspiration for The Fisher Lass, 1999, evoking the dramas of those who are born to the fishing way of life and described by the publishers as ‘…a love story as powerful and restless as the mighty North Sea’. Spalding and district was the background for The Tulip Girl, 2000, and The River Folk, 2001, was inspired by Margaret’s birthplace, Gainsborough.

Tangled Threads, a story set in the Nottinghamshire framework knitting and lace industries in the early 1900s, was published in 2002 and its sequel the following year. Twisted Strands followed the lives of the same characters affected by the Great War. Margaret’s novel for 2004, Red Sky in the Morning, returned to the Lincolnshire Wolds and evoked the era of the Second World War and its aftermath.

The Workhouse Museum at Southwell in Nottinghamshire was the inspiration for Without Sin, 2005. As always, Margaret’s characters and storylines are completely fictitious, though the background research at the museum was fascinating.

Pauper’s Gold, 2006, is an emotional story of love and survival, set in a Derbyshire cotton mill and the silk town of Macclesfield. In the 1850s life was harsh for the pauper apprentices, children taken from workhouses and bound to their masters for years. And, with the onset of the American civil war, a cotton famine caused greater hardship in the mills of England.

Wish Me Luck, 2007, is set on a Lincolnshire bomber station in the Second World War. The shout line on the book cover says it all: Love and Laughter, Tears and Courage in a Time of War. Sing As We Go, 2008, too had a World War II background. The heroine, after personal tragedy and heartache, joins a concert party to entertain troops, hospital patients and war workers. In Suffragette Girl, 2009, the story travels from Lincolnshire to London, the trenches of the Great War and then to Davos in Switzerland.

To celebrate the Millennium, Margaret was invited by Skegness Playgoers to write a community play. Embracing Tides, featuring the life of a fictional family throughout the twentieth century in Skegness, was staged at the Embassy Theatre in November and December 2000. It was also the Playgoers’ entry for that year’s Play Festival. The production won five of the Festival’s thirteen awards.

Margaret’s stories focus on key and strong women and the roles that they have completed over the centuries ranging from Buffer Girls to Suffragettes, she has a talent of making those stories come alive. Her most recent works include The Poppy Girls, The Brookland Girls and The Spitfire Sisters. The Poppy Girls was an amazing tribute to the nurses that worked tirelessly on the frontline during the First World War.

Julia Deakin became one of the Heritage Association’s Vice Presidents and re-opened the Gainsborough Heritage Centre after a project to create new permanent displays in 2016. She was born in 1952 in Gainsborough and is a British actress. On television, Julia played Stella Tulley in Side by Side and Marsha, the ageing but lovely divorcée rock chick landlady, in the British sitcom Spaced (1999). She also had cameos in the feature films Shaun of the Dead (2004) and Hot Fuzz (2007).

Julia Deakin

Julia earlier appeared in the television sitcom Oh, Doctor Beeching! (1996 – 1997), where she played the role of May Skinner. She has also made many single television appearances, including playing Jill, the receptionist from Pear Tree Productions, in one episode of the first series of I’m Alan Partridge, a rural dominatrix in Doc Martin as well as roles in Midsomer Murders and Coronation Street. She appeared in the sketch comedy series Big Train alongside fellow Spaced cast members, Simon Pegg and Mark Heap.

Julia has also appeared on radio, in the Radio 4 science fiction comedy Nebulous. She also guest-starred in the Doctor Who audio drama Terror Firma for Big Finish Productions. Her most recent work is as pub landlady Mary Porter in the film Hot Fuzz by Simon Pegg and Edgar Wright. She is married to the actor and author Michael Simkins.

- Our new Vice President Julia Deakin with the official opening plaque

- Julia Deakin giving her speech at the opening

Julia Deakin pictured above in 2016 re-opening the Gainsborough Heritage Centre. If you would like to read more about the opening click here for the full story.

Alison Brackenbury was born in the town in the year 1953 but was raised in the nearby village of Willoughton, a short distance away. It was here that she attended the village school for her early education before going on to attend Brigg High School. Alison finished her education attending St Hugh’s College, Oxford where she studied for a degree in English.

Alison Brackenbury

Alison moved away from Lincolnshire around 1975, she married soon after and now resides in Gloucestershire. Not long after being married, she went to work as a Librarian in a Technical College, a role she enjoyed for several years between 1976 and 1983. In 1985 she became a part-time account and clerical assistant and stayed in this role until 1989, after this she worked hard as a Director and Metal Finisher in the Family Business. Alison successfully fulfilled a role as mother to her one daughter and became a well respected and published poet and author.

Her first collection was published in 1981 called “Dreams of Power” followed a few years later by another collection and many more since (see below for full listing). Many of her works have also appeared on BBC Radio and most notably her “1829” was produced by Julian May for BBC Radio 3.

In 1982 Alison received a prestigious Eric Gregory Award from the Society of Authors awarded to British poets under the age of 30 on the basis of a submitted collection. More recently in 1997 she also received a Cholmondeley Award another honour from the Society of Authors given annually to honour distinguished poets.

Her poetry has appeared in Agenda, PN Review, Poetry Review, The Times Literary Supplement and Magma among other magazines. She also judged Plough Prizes, 2004 and 2005 and the National Poetry Competition, 2005.

Alison wrote a passage on her thoughts of Gainsborough in 2009 for the publication ‘Famous Sons and Daughters of Gainsborough by Andrew Birkitt.’

‘Gainsborough’. What does the name recall to you? I immediately see the red sweep of Marshall’s works. Every time we drove slowly past the long brick walls, my mother would say, ‘That’s where your grandfather used to work.’ Having survived the whole of the First World War, he became a partially colour-blind electrician, followed around by an apprentice who checked the colours of his wires. He also, I believe, fell off Marshall’s roof – and survived.

Dark in my mind’s eye, too, is another survivor, the wooden ark of the Old Hall. I was told that Civil War silver had been dug from its cellars’ earth. I was fascinated by this but frightened by the black flood marks at Gainsborough’s waterside. It is no coincidence that I have just written a poem called ‘Flood’.

The first (very small) supermarket opened in Gainsborough during my childhood. Yet there were still many small shops, including an underwear shop where I first saw a pair of tights. Surely they would never catch on? And was it Boots which still had a faded sign for their Subscription Library?

Gainsborough’s Public Library was vital to me. I found a footnote in a school textbook about James I’s cousin Arbella, whose short and little-known life mixed folly, courage and love. The patient librarians at Gainsborough ordered book after book for me, including Victorian editions of her letters. Thirteen years later, now married and living in Gloucestershire, I sat down to write a poem about Arbella called ‘Dreams of Power’. It drew, as poems often do, on well-worked memories, including those leather-bound books. It became the title poem of my first published, prize-winning collection: ‘a vivid new talent’ said ‘The Sunday Times’. Grey-haired now, muddling through my own industrial job, while drafting a BBC talk and my eighth book, I still have a particular fondness for that poem. I am very grateful to Gainsborough.

References

- Famous Sons and Daughters of Gainsborough & District, by Andrew Birkitt, June 2009. Anne Mozley (17 Sept 1809 – 27 June 1891), Dame Agnes Sybil Thorndike CH DBE (24 October 1882 – 9 June 1976), Margaret Dickinson (1942), Julia Deakin (1952) and Alison Brackenbury (1953).

- Nursing Midwifery & Me by Phyllis Peart (2015).

- Connie Kirk newspaper article information and images courtesy of Paul Kemp.

- Information on Daisy Girdlestone courtesy of the Gainsborough Heritage Centre Archives.

- The Secret History of Women and Journalism, by Sarah Zama.

- NC Theatre, Women in Theatre: A Historical Look, posted in 2015.

- Women in Photography: a Story Still Being Written, by Dawn Oosterhoff in March 2017

- Fawcett Society, Women’s Rights Timeline.

Thank you for reading. Please note the Heritage Centre is currently closed due to the Cornavirus pandamic.