Built by Sir Thomas Burgh around 1460, Gainsborough Old Hall is a beauty and true hidden gem. It was not only a home for the Burgh family, but also a status symbol- with Thomas presented with multiple positions from and in numerous Royal households, including being named Sheriff of Lincolnshire, ‘Heart of the King’s Court’ (both rewarded by Edward IV), Knight of the Garter for Richard III and Knight of the Body for Henry Tudor. As well as his Knighthood and Lordship.

Thomas’ descendents weren’t always as equally successful, though many still retained titles in the Peerage and great success. A common talking point regards Edward Burgh (1508-1533), Thomas’ Grandson, who married Catherine Parr in1529, both living in the house until 1530. Just 4 years into their marriage Edward met his untimely death and Catherine went on to marry John Nevill, 3rd Baron Latimer, before her famous marriage to Henry VIII. Throughout the Burgh’s ownership they and the manor entertained some well esteemed guests, including Richard III in 1484 and Henry VIII, once in 1509 and a second time along with his fifth wife Catherine Howard, in 1541.

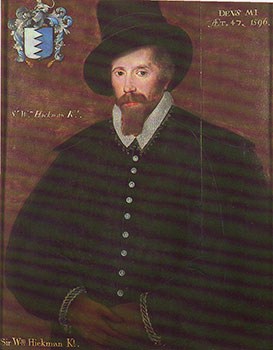

The Burgh family, with Thomas’ 5 children, and subsequent descendents, used the manor for many years until the 5th Lord Burgh died in 1596, leaving no heir, when it was sold on to the Hickman family.

William Hickman bought the house in 1596, to the East Wing he added a number of bedrooms and a Panelled room, in addition to other all round improvements on the house. Other than this, the house has barely changed since it’s original fixes in 1469 after damage from an invasion of Lancastrian troops and slight extras since such as Victorian tiles in the Great Hall.

William Hickman bought the house in 1596, to the East Wing he added a number of bedrooms and a Panelled room, in addition to other all round improvements on the house. Other than this, the house has barely changed since it’s original fixes in 1469 after damage from an invasion of Lancastrian troops and slight extras since such as Victorian tiles in the Great Hall.

With William’s support, the separatist John Smyth (considered a founder of Baptist Churches) often met and worshiped at the Hall before his journey to Holland to further study and spread the word of the Bible. The Hickman family’s support of religious movements also included that of John Wesley, a founder of Methodism, who preached at the Hall in 1759, 1761 and 1764; though by this time, the new Thonock Estate had been built and the Hickman family rarely used the Hall for themselves, it began to fall into disrepair.

Following the major households, the Hall began to be used in varying ways. Parts, mainly that of the West Wing, were divided up into tenements, let out to land owners and townspeople, whilst the East Wing was let more commonly as apartments. Over the years workshops were also set up for such trades as joinery, bricklayers and coopers, a public house, the Queen Adelaide took up residence in the West Range and the kitchen was used as a soup kitchen during the harsh winter of 1816. In 1790 the Hall became a coarse linen factory, leased by William Hornby, the first bank owner in the town, though it was not successful and instead he too let parts of the building. One such letting was of the Hall for £50 a year to Mr West who used it as a theatre. The theatre was so successful it ran until 1849, and would have continued, if not for Sir Henry Bacon Hickman who outmanoeuvred the company to take ownership and turn the Hall into a corn exchange. Sir Hickman once again restored parts of the Hall as well as his nephew and great nephew, Hickman Beckett Bacon. Between 1896 and 1952 the Hall was used by the Freemasons as a Masonic Temple and supported by an in house caretaker, lodging in the East Range. It was after the caretaker’s death and further disuse that the house became so dilapidated it was a shadow of its former self. Gratefully, it was taken up by Harold Witty Brace, founding the Friends of the Old Hall, who collectively saved the building from complete destruction following plans of flattening and converting the site into a car park during the 1950s. The group worked tirelessly to renovate and save the building, funding urgent repairs and further income to keep the Hall running. The Old Hall is now a museum and, may I say, an absolute beauty to behold, inside and out.

As one of the best preserved and working kitchens of its period in England, Gainsborough Old Hall’s kitchen is a sight not to be missed. Along with the Great Hall itself, it is one of the focal points of the manor and there is no question as to why.

As with many houses, the kitchen was the heart of the house and was constantly busy with staff preparing food, cooking, baking and setting it out to impress the Lords and their visitors.

The Kitchen stands much as it would at the height of it’s day, the serving hatch greeting the workers as they enter from the Great Hall, the small work and living rooms on the upper level, only accessible by ladders from those below, and the cooking facilities around the room; two large fireplaces and the bread ovens. It is said that the serving station would have once been uncovered, with the space between the Hall and the Kitchen separate, most likely in case of fire and the attempted prevention of the flames catching onto the main building of the Hall. Over time, it was covered up and is as can be seen to this day. Whilst the kitchen remains relatively close to its original build, there has, of course, been renovations and alterations over time, with new owners building buttresses and other such structural improvements, altering walls and adding walkways leading from the exterior to the Buttery and possibly other rooms (now no longer standing, but prints still remain of these having being in situ in the 18th or 19th centuries, a number of such available to view here at the Heritage Centre). The room is mainly built from brick, and timber is only in use where fire risk is minimal, such as the high roofing and the louvre. The louvre within the roof acted as a ‘chimney’, being slatted in a similar style to modern blinds, allowing staff to open it or close it further depending on the amount of smoke, inside, and wind, outside. A louvre was also in place within the Great Hall roof, allowing the smoke from the central fire to escape, though this became structurally unsound and was taken down in the 50’s to be exhibited in the East Range.

As for stocking and food production, many meats came from the surrounding land, either farmed, hunted or caught from the Trent. Farm animals were butchered in the Autumn, allowing them to save on feeding over the Winter, and then preserved for the following year ahead. Such preservation techniques included drying, pickling and salting. These meats, as well as the fish preserved in the same way, were often used in stews for the Winter, and boiled in large pots. The fireplace to the right was used for such stews, whilst the larger roaring fire on the left was solely for the hunted meat, placed onto spits. This would include the wild boar and deer from the land that once surrounded the Hall and town.

There is a room to the left of the bread ovens that served as a preparation area for the dough, which was then placed on wooden peels and carried through to the ovens. Fires were lit within the ovens, heating them. The resulting ashes were shovelled out allowing space for the bread, moved into place by the peels before being enclosed with mud sealed doors fitted into the openings.

Of course, there had to be displays of wealth, produced by the presentation of the food as well as the building around them. Peacock was among the large birds, with feathers replaced after roasting, along with the beaks of swans gilded to add to the wow factor. Sugar, marchpaye (marzipan) and jelly was often used in models and outstanding creations to also show such importance. Examples of such models were beasts, real and mythical, and castles.

The kitchen, once a bustling workplace, producing the household’s food and serving as yet another example of wealth and importance, is still as absolutely amazing to gaze upon today, just a little quieter.

Comments(2)

Emily Vessey says

29th October 2016 at 10:38 pmExcellent, well-researched article. Gainsborough and it’s Hall played such an important role in English history during the 15th, 16th and 17th centuries which isn’t recognised nearly as much as it should be, especially as the area is so closely linked to the Separatist movements of pilgrims that emigrated to, and founded, the United States, and later the Methodist movement led directly from the Hall by John Wesley. I just wish the Hall had more funding so it could host more events than it does and really play on its international connection, as well as more Tudor and Jacobean-themed events. I believe the staff who run it are mostly volunteers and are excellent. I’ve been in about 10 or 15 times over the last 25-30 years and some displays could do with re-imagining, as very little has changed in this time. However, I like that the museum has not had a technology-based makeover but there are other ways it could benefit from investment. I’m glad they have opened up the Stewards room above the servery, as only a few years ago, this was an inaccessible over-crowded storeroom for much of Gainsborough’s historical artefact collection, the majority of which I believe has been transferred to Lincoln’s archive. It really needs English Heritage to properly invest as they always do with properties in more densely tourist areas, particularly those further South.

Rea Long says

5th February 2021 at 12:06 amI would love to know if a portrait of sir Thomas Burgh exists, as it seems I am related to him through my paternal grand fathers side.

Recent posts

Events