Charles William Clarke

Charles William Clarke was born on 29th September, 1895 at his grandparents’ house in Gainsborough. Charlie, as he was known, lived with his family at 2 Gladstone Cottages, Morton. He attended Morton School, which he left in 1909 at the age of 14. In 1912, Charlie started work at Marshall Sons & Co. Ltd, Gainsborough as a foundry apprentice. His apprenticeship, however, was put on hold when he enlisted into the 8th Battalion, Lincolnshire Regiment on the 1st September, 1914, a month after war had been declared. This was part of Kitchener’s New Army, and he was one of nearly 1.2m new recruits who had volunteered by the end of the year. Only in January 1916 was conscription finally introduced.

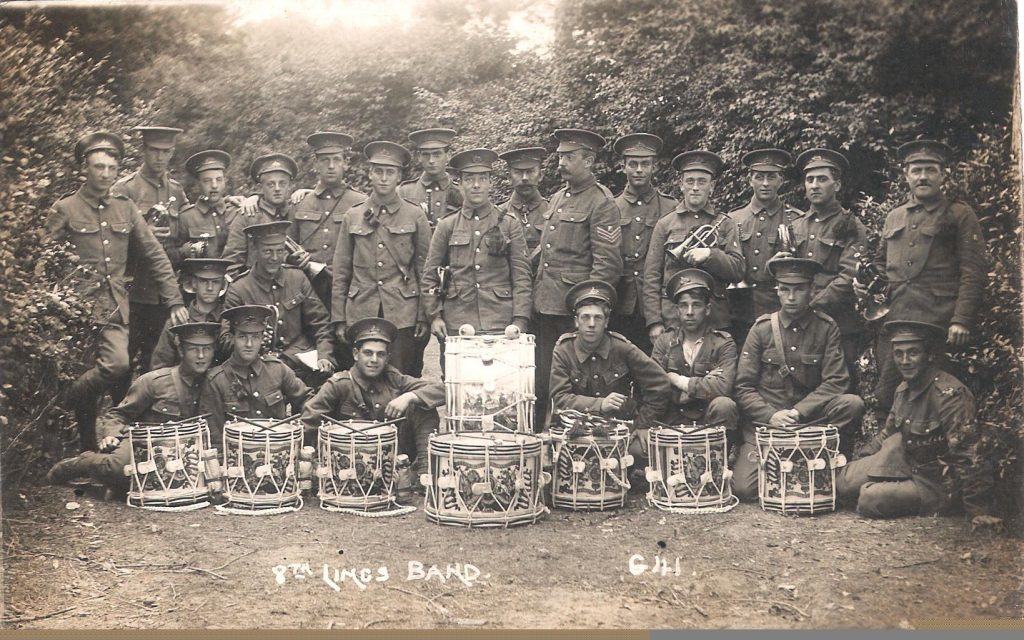

Paid one shilling a day as a drummer, Charlie was sent to France with his Battalion in August 1915 and fought in the Battle of Loos and the famous Hill 60 engagement. Only a month later, on the 26th September, 1915, he was wounded and taken prisoner. After being released from hospital in Germany he was sent to work down a coal mine but due to health problems was later transferred to a farm. Charlie sent letters and postcards to his future wife, May Evelyn Wright which sheds light on his daily experiences. Many of the postcards are from the period when Charlie was a Prisoner of War. Some, however, are from an earlier period when he was training and when he was first sent to France.

Young men volunteered for many reasons: out of a sense of patriotism and duty, pressure, for the adventure, because they were stuck in monotonous jobs or unemployed. Few predicted or could have imagined what was to follow. Initially the training provision was poor; weapons were in short supply. Many volunteers also thought the war itself was going to be short. Charlie was one of those young men. He wrote later from his training camp:

Dear May

… We have started firing with ball cartilage now and it gives you a nice black shoulder with the force that comes back from it…. [It will] not be long before we are in France. We have finished all drills now we are firing we starte at half past 4 in the morning while seven at night and it make you nearly deaf. We are having some very nice weather down here now I … wish I was at home on Sunday so we could have a nice walk and enjoyin ourselfe like we use to do but never mind the time will come when the war is over. I think it will not be long now before it is all finished. I will close now with love From your loving Sweetheart

Charles Clarke xxxxxxx

You are a long while sending me a photo

Charles william Clarke 5th from left back row 5th Lincs band

Letters, of course, were meant to reassure loved one’s back at home. Private soldiers, too, were aware that their letters were censored, and what they could and could not say. Arriving in France, he wrote:

Dear May

We arrive safe and sound and are quite happy and livly. We are billited in a barn. I cannot write very much as they read all the letters before they come over the sea. We had a lovely boat ride it went nice and smooth we went over in the dead of night. We camped out the first night and then went further in the country. There are a lot of fine blackberries round this part. I cannot write anymore now.

From your Loving S H

Xxxx Charles Clarke

Some grumbles, however, did creep through: ‘I have been on guard 2 time since Sunday and I am getting tired of them for you have to stop up all night to that these is fire if there was I should have to bugle the fire alarm…. all the Companys are doing night work they go out at 4 o’clock and come in about 1 in the morning and they think they are working them over much’, finishing ‘ Have you had your photo taken yet if you have would you mind sending me one. Give my love to all at home.’ x

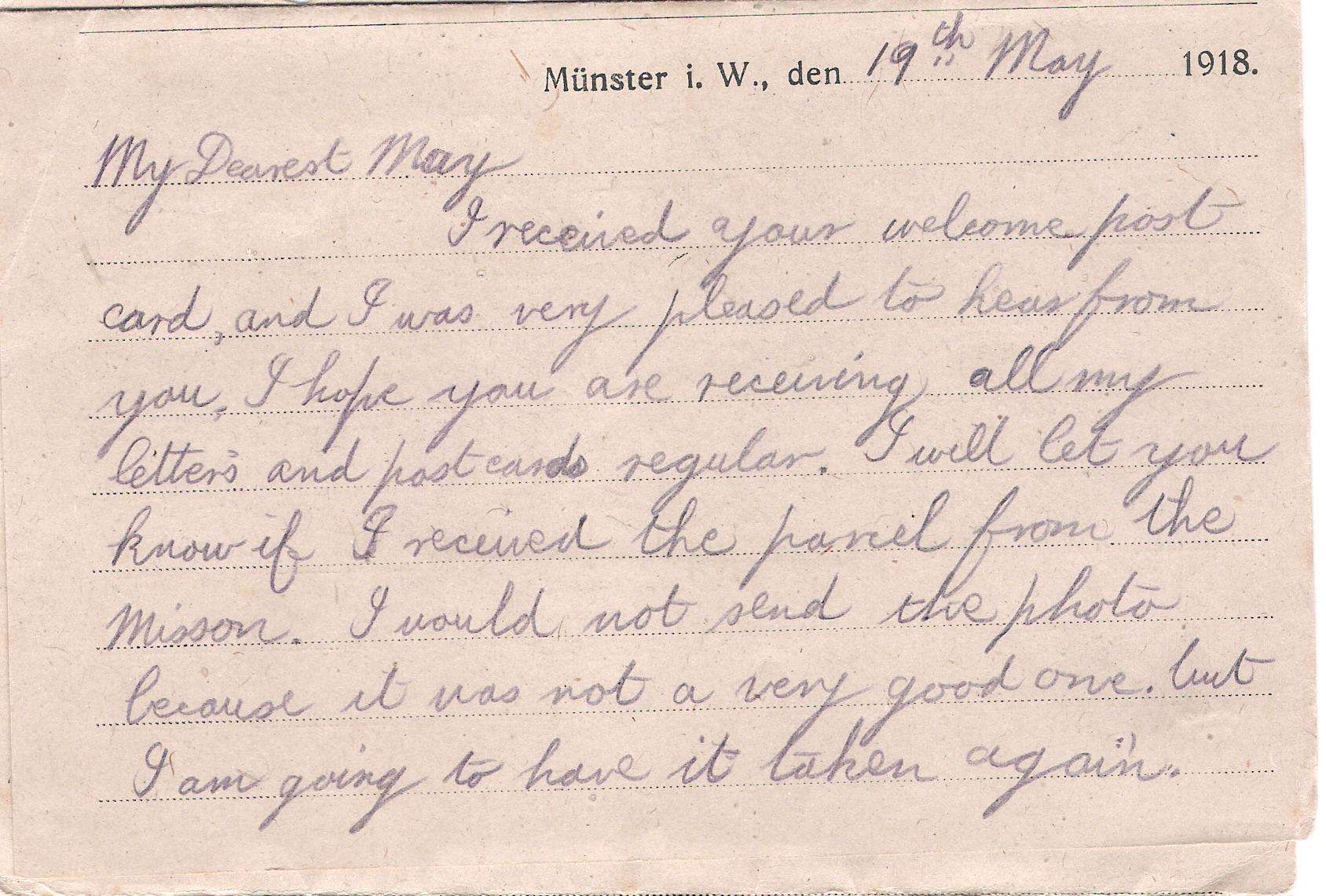

Letter from Charles William Clarke 19th May 1918

His postcards when a PoW were generally even more brief, formulaic and perfunctory, governed by circumstance, immediate priorities and space. Only occasionally did raw emotion show through. Away from his family and future wife, he was so young to be living the life that so many others lived also for this period of time. Shortly after his release from hospital, he wrote, ‘I thank you very much for the parcel it was in a good condition and the cake’s was lovely. I thank you for the razor blades they just fill my razor and the cigarette I enjoyed them too.’ A few months later, he penned:

Dear May,

I received your letter and was pleased to here from you I am sorry I have not written to you for a week or two. I have a letter from the American Express to say that you are sending me a parcel which I thank you very much for. I will let you know when I receive it. It will be my twenty first birthday this month. Will you tell mother that I am in the best of health and Remember me to all at home Well Dear I think this is all I can write this time.

From Your Loving Sweetheart Charles.

There was comment aplenty on the state of the weather: ‘very bad weather again now’; ‘some good weather now after plenty of rain’; ‘having some grand weather just now’, and We are having very funny weather just now’; and a quick comment that ‘and my hand is just about better.’ ‘Remember me to all’, ‘I am quite longing to be home again and to be with you’, and then finally, in November 1918, ‘I have arrived in Holland today and I am quite well. Look out for me in a few days times. Keep Smiling.’

But prolonged separation also brought problems, anxieties and tensions. Just before his release the news from home was less good, less comforting:

May dear May,

I received your welcome letter on the 28th June and was very pleased to hear from you. I wrote to you for this last six weeks and you say you were three months without a letter. I have always wrote to you and more than to anyone. I sent three photos home one is for you. I hope you will like it. I will close now.

Your’s Truly Charles Clarke xx

And…

Dear May

I am writing these few lines hoping you are in the best of health. I received your letter dated the eleven of July and one of the 6th of august. The one for the eleven it quite upset me I can tell you. Yes, I write to Miss Hartley, and why not. She is a very good Lady, who is paying for my parcels and bread, her home is at Jersey, I have also got her photo, and when I come home I will let you see it, and you can see for yourself- which of you two I want. Well Dear you think I have forgotten you, but that I can never. I have sent you letters and cards regular, and I am very sorry if you have not received them. Well Dear you can sent me your photo, I shall be very pleased to received it I can tell you. We are having some very changeable weather just at the present but I hope it will clear up a bit. Well Dearest cheer up and keep smiling, the sun will shine someday, when I come home, and to be with you I think I have told you all this time.

From Yours Ever Loving Charles.

Charlie returned to marry May, and to complete his apprenticeship at Marshalls on the 10th March, 1919. He worked in the foundry as a core maker until he was made a foreman at the age of 60. About two years later he was promoted to Apprentice Supervisor looking after the Foundry apprentices, a job he really loved and enjoyed. Unfortunately, he was taken ill in the August of 1960 just before his 65th birthday and died on New Year’s Eve of that year. Just before he died he received a letter from the Queen awarding him the British Empire Medal. His son, Harold Clarke remembered that ‘he very seldom talked to the family about his experiences as a Prisoner of War but I do recall him saying that the farmer’s wife was very good to him and fed him well.’

Charles William Clarke as a Prisoner of War