The Second World War began in Europe on September 1, 1939, when Germany invaded Poland. Great Britain and France responded by declaring war on Germany on September 3. The war between the U.S.S.R. and Germany began on June 22, 1941, with the German invasion of the Soviet Union. The article below is going to share the memories of Gainsborough people who experienced the War living in the town or local nearby villages from the Oral History Archives at the Gainsborough Heritage Centre.

Derek Farr born in 1931 lived in East Stockwith during the Second World War and he recalls the day War broke out in the first clip below. Derek also recalled a lot of activity that happened in the village of East Stockwith during the War years. At this time it was said, that ‘Careless Talk Costs Lives’ so the people of Gainsborough probably would have had no idea of what was happening in nearby East Stockwith. In the clips below Derek explains his memories of being a child and watching with much fascination with his group of friends as the Army built massive pontoon bridges across the River Trent. The Army at this time was practising for when they would need to build bridges in areas such as the Rhine so that military vehicles or tanks would be able to cross difficult waters in the battlefields. A pontoon bridge also known as a floating bridge, uses floats or shallow-draft boats to support a continuous deck for pedestrian and vehicle travel. The buoyancy of the supports limits the maximum load they can carry. Most pontoon bridges are temporary, used only in wartime and civil emergencies.

Derek Farr Oral history interview, 2018

Derek continues with his story of the Pontoon bridges with memories of the Army also practising building pontoon bridges at the small village of Walkerith.

Derek Farr Oral history interview, 2018

During the Second World War, many factories or modes of travel to other places such as the railways or bridges were potential targets for enemy aircraft. The Association’s Chairman Andrew Birkitt has written a fantastic article this week about the role of Marshall’s in the production of X-Craft Midget Submarines (The Daring Exploits of a Gainsborough Built Machine). The Midget Submarines were just one example of the towns War production at that time making Gainsborough a key target for raids.

Enid Burrell recalls her recollections of the Midget Submarines and her Father’s work below:

Enid Burrell Oral history interview, 2017

Jim Page worked in the Planning Department working on Post-War Planning for Gainsborough and he has shed some light on how the Ministry of Works planned many defences to secure the town of Gainsborough in the event of an attack from the Nottinghamshire side of the river. Jim kept these secrets for over 30 years due to the Official Secrets Act, please click on the clips below to find out more from Jim with an interesting story about Gainsborough’s Trent Bridge on clip two.

Jim explains more about his role in the Planning Department in the clip below:

Jim Page Oral history interview, 2017

Blackout regulations were imposed on 1 September 1939, before the declaration of war. These regulations required people to make sure that all windows and doors were covered at night with a suitable material such as heavy curtains, cardboard or paint, to prevent the escape of any glimmer of light that might aid enemy aircraft. Street lights were switched off or dimmed and shielded to deflect the light downward. Traffic lights and vehicle headlights were fitted with slotted covers to deflect the beam down to the floor. Blackout brought a massive change to society as it made life more difficult navigating at night and unfortunately thousands of people died in road accidents. The number of road accidents increased because of the lack of street lighting and dimmed traffic lights. To help prevent accidents white stripes were painted on the roads and on lamp-posts. People were encouraged to walk facing the traffic and men were advised to leave their shirt-tails hanging out so that they could be seen by cars with dimmed headlights. Other people were injured during the Blackout because they could just not see in the darkness. Many people were injured tripping up, falling down steps, or bumping into things. Derek in the clip below recalls the blackout in East Stockwith village near Gainsborough.

Derek Farr Oral history interview, 2018

Like most places, Gainsborough’s popular social activities included dancing and attending the pubs and there were a lot more pubs in Gainsborough at that time. Joyce Thompson born in 1926 explains how she enjoyed dancing and the air raid sirens never stopped her and her friends dancing!

Joyce Thompson Oral history interview, 2018

As mentioned earlier in the article, Gainsborough was a target for bombing and air raids due to its industry and production for the war effort as well as Lincolnshire’s role as bomber county meaning that there were a large amount of air bases in the area so accidents with aeroplanes did occur. Luckily, there were not many bombing raids on Gainsborough, but in the oral history clip below there are some recollections in particular of the Market Street Raid in 1942. Derek continues below by recalling his memories of hearing bombs and seeing aircraft from East Stockwith.

Derek Farr Oral history interview, 2018

Norman Antcliff born in 1930 lived on Stanley Street in Gainsborough and recalls how as a boy he used to remember collecting shrapnal from bombs with his friends.

Norman Antcliff Oral history interview, 2015

Flying conditions over Gainsborough on the afternoon of the 22 May 1944, were very bad due to thick industrial haze. A Wellington bomber flew over the town, taking evasive action as a Spitfire of an Officer Training Unit made mock attacks upon its target. This ‘Camera Gun Training’ was commonplace over Lincolnshire during the war and it would not have created much interest among the townspeople going about their daily business. However, the noise of a mid-air collision drew attention to the fighter diving out of control and eventually colliding with a Sheffield bound good train, passing over the Lea Road, Ashcroft Road railway bridge. The main body of the wreckage landed on the railway bank, with some striking the gable end of a dwelling house on Lea Road. The Gainsborough Fire and Rescue Services were soon in attendance, followed quickly by Royal Air Force tenders from local airfields. The pilot of the Spitfire was killed, but there were no more causalities. Norman remembers this event and the aftermath:

Norman Antcliff Oral history interview, 2015

Gainsborough received its first direct attack in the early hours of the morning on the 29 April 1942. A Dornier 217 bomber approaching from the North West dropped a stick of 500kg G.P bombs on the Town Centre. Damage to property was severe. Buildings fronting Market Street, Church Street and Roseway were demolished and Heaton Street ceased to exist. The raid caused problems for the Ministry of Food when a large cold store, containing most of the town’s meat rations was completely wrecked. By the end of this raid, the destruction caused is shown: 39 shops and businesses damaged; one public house; one hotel; the billiard hall, cold store and a row of dwellings. There was widespread blast damage to a large area of the town, including the telephone exchange and the front wall of the Town Hall which had to be re-built.

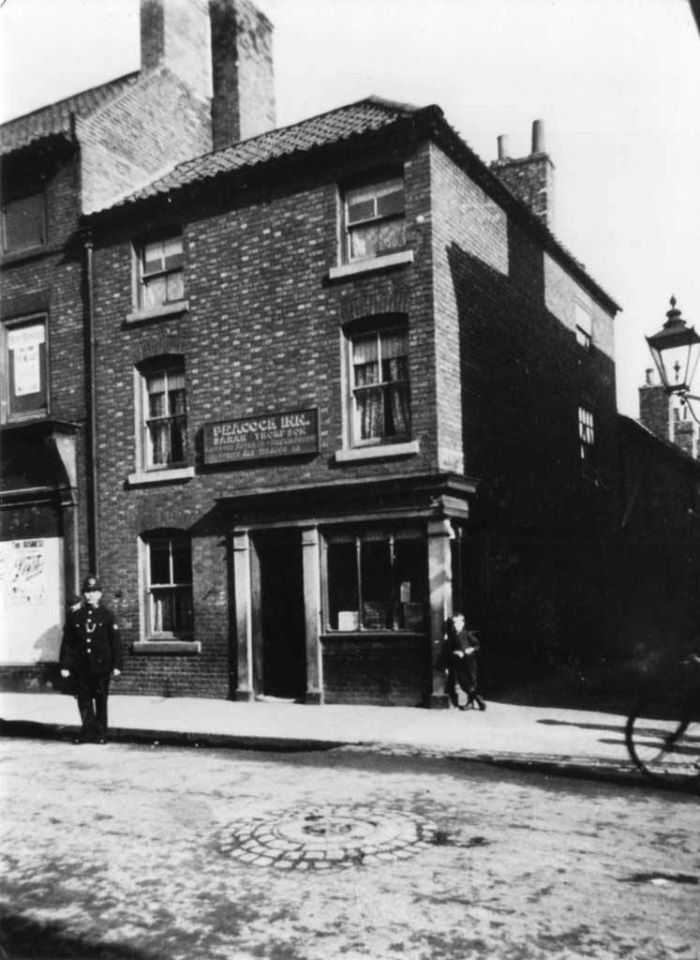

Seven people were killed and six seriously injured. Four soldiers of the Leicestershire Yeomanry died when their Sergeant’s mess received a direct hit. Civil Defence Rescue Services found their efforts hampered by coal, gas and water from fractured pipes, but managed to rescue survivors before daylight. Mr and Mrs A Coulson, the licensees of the Marquis of Granby died when their hotel was demolished. Mr Ralphs, a tailor by profession, was also killed. The rescue services were unable to free his body until the next day. An innkeeper and his wife of the Peacock Inn managed to crawl out of their bed and were rescued after clinging to a tilting bedroom floor when the front of the building had been blown off. There was a fire in a tobacco warehouse which was brought under control by the fire service. The residents of a row of cottages were fortunate to escape serious injury when their homes were completely wrecked. However, there was no interruption to the production in the factories. Marshall’s engineer’s extension did suffer from the blast damage to the windows and roof, but luckily there were no causalities.

Peacock Inn

In the civil defence headquarters, no air raid warnings had been received and no condition red was in operation in the county of Lincolnshire. The only explanation found for this raid on Gainsborough was another raid that was taking place in the city of York. This raid was the only action in the north of England that night, so ultimately it went wrong and the plane was looking for an alternative target. The aftermath of this raid still caused problems for Gainsborough as the question was, was there an unexploded bomb included in the stick? A thorough search was carried out over the whole area but nothing was found. Following the raid, the local council held a meeting at which tributes were paid to the Civil Defence Services and military personnel for their efforts after the raid was over.

Norman Antcliff Oral history interview, 2015

Phyllis Peart Oral history interview, 2015

Harry Barrett Oral history interview, 2017

An interesting story from Rosemary Speck tells us about her two sons who many years after the War were playing in the area near Tennyson Street and located an unexploded bomb!

Rosemary Speck Oral history interview, 2015

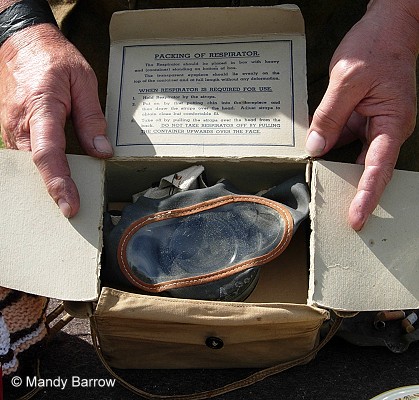

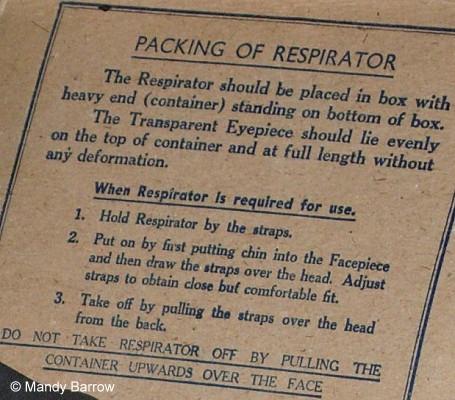

By September 1939 some 38 million gas masks had been given out, house to house, to families. Luckily, they were never to be needed. Everyone in Britain was given a gas mask in a cardboard box, to protect them from gas bombs, which could be dropped during air raids. Gas had been used a great deal in the First World War and many soldiers had died or been injured in gas attacks. Mustard gas was the most deadly of all the poisonous chemicals used during World War I. It was almost odourless (could not be smelt easily) and took 12 hours to take effect. It was so powerful that only small amounts needed to be added to weapons like high explosive shells to have devastating effects. There was a fear that it would be used against ordinary people at home in Britain (civilians).

The masks were made of black rubber, which was very hot and smelly. It was difficult to breathe when wearing a gas mask. When you breathed in the air was sucked through the filter to take out the gas. When you breathed out the whole mask was pushed away from your face to let the air out. The smell of the rubber and disinfectant made some people feel sick. To warn people that there was a gas about, the air raid wardens would sound the gas rattle and to let people know it was all clear they would ring a bell.

Shirley Dawe born in 1936 remembers receiving a gas mask and participating in practice drills at school. Learn more about Shirley’s experience in the clips below.

Shirley Dawe Oral history interview, 2017

- OLYMPUS DIGITAL CAMERA

Mickey Mouse Gas Mask

Joyce Thompson Oral history interview, 2018

The first German air attack took place in London on the evening of 7 September 1940. Within months, Liverpool, Birmingham, Coventry and other cities were hit too. As the night raids became so frequent, many people who were tired of repeatedly interrupting their sleep to go back and forth to the shelters virtually took up residence in a shelter in larger cities.

Anderson Shelters were shelters that were half-buried in the ground with earth heaped on top to protect them from bomb blasts. They were made from six corrugated iron sheets bolted together at the top, with steel plates at either end and measured 6ft 6in by 4ft 6in (1.95m by 1.35m). The entrance was protected by a steel shield and an earthen blast wall. The government gave out Anderson shelters free to people who earned below £5 per week. By September 1939 one and a half million Anderson shelters had been put up in gardens. The Anderson Shelters were dark and damp and people were reluctant to use them at night. In low-lying areas, the shelters tended to flood and sleeping was difficult as they did not keep out the sound of the bombings.

Derek Farr recalls his family attempting to dig an Anderson Shelter in the clips below:

Derek Farr Oral history interview, 2018

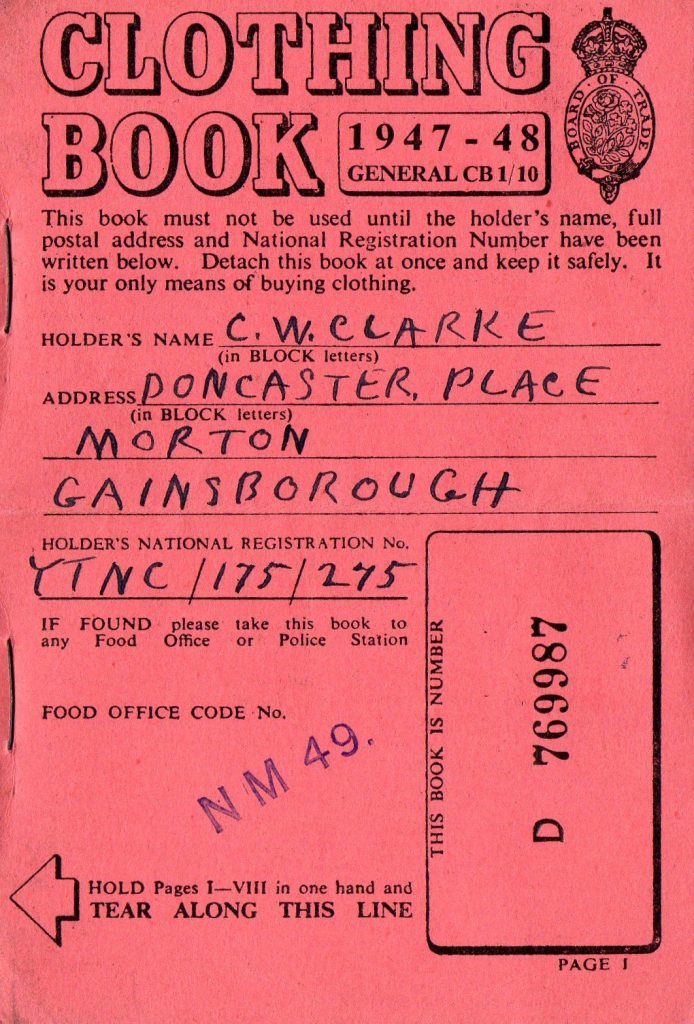

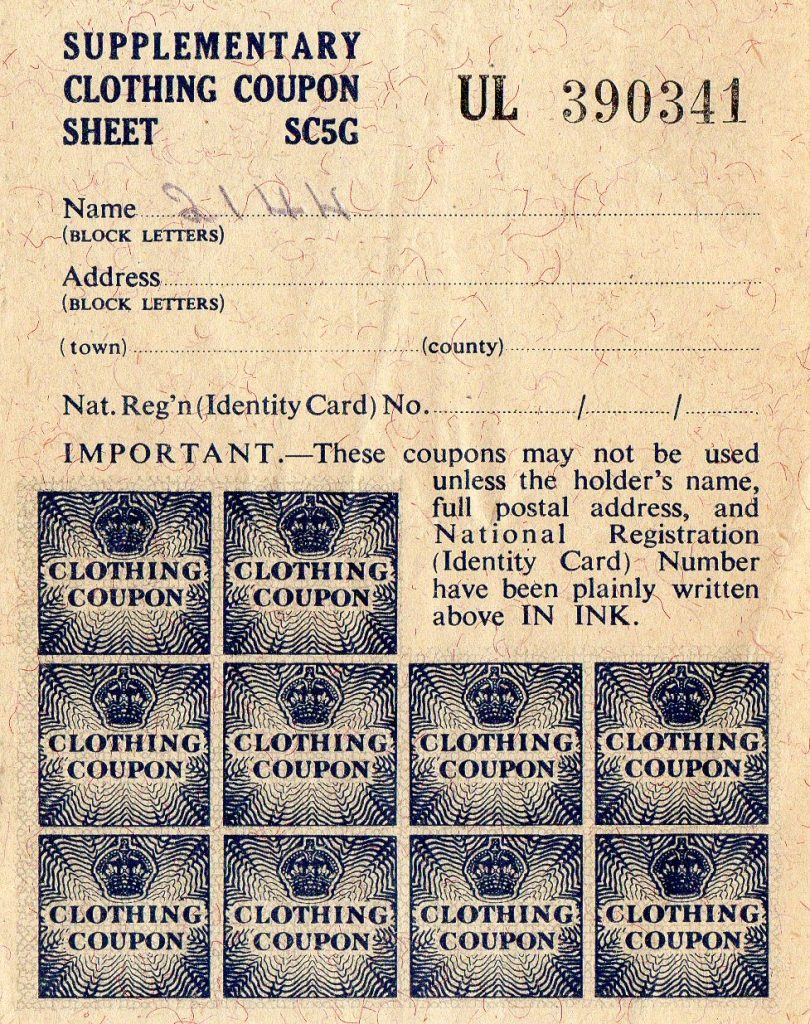

During World War II all sorts of essential and non-essential foods were rationed, as well as clothing, furniture and petrol. To make the British weak, the Germans tried to cut off supplies of food and other goods. German submarines attacked many of the ships that brought food to Britain. Rationing was introduced at the beginning of 1940.

Before the war, Britain imported 55 million tons of food, a month after the war had started this figure had dropped to 12 million. The Ration Book became the key to survival for nearly every household in Britain and every member of the public was issued with their own ration book. The books contained coupons that shopkeepers cut out or signed when people bought food and other items. The colour of the ration book was very important as it made sure you received the right amount and types of food required for your health. The books contained coupons that had to be handed to or signed by the shopkeeper every time rationed goods were bought. This meant that people could only buy the amount they were allowed.

Buff-coloured ration books tended to be for the majority of adults however, green ration books were produced for pregnant women, nursing mothers and children under 5. They had the first choice of fruit, a daily pint of milk and a double supply of eggs. Blue ration books were for children between 5 and 16 years of age. It was felt important that children had fruit, the full meat ration and half a pint of milk a day.

The government was worried that as food and other items became scarcer, prices would rise and poorer people might not be able to afford things. There was also a danger that some people might hoard items, leaving none for others. Fourteen years of food rationing in Britain ended at midnight on 4 July 1954, when restrictions on the sale and purchase of meat and bacon were lifted. This happened nine years after the end of the war.

Shirley Dawe recalls in great detail her memories of rationing during the War in the clips below and the food that they had available in Gainsborough:

Shirley Dawe Oral history interview, 2017

Joyce Thompson Oral history interview, 2018

“Dig for Victory” was the hugely successful propaganda campaign that encouraged civilians to grow their own in order to reduce Britain’s reliance on imports. In the 1930s 75 per cent of pre-war Britain’s food was imported by ship and the German U-boat blockade threatened the home front with starvation.

Derek Farr Oral history interview, 2018

Shirley Dawe Oral history interview, 2017

During World War II, many sets of iron railings in Britain were removed. Railings were usually cut off at the base; the stubs may still be seen outside many buildings where they have never been replaced. This was supposedly to provide scrap metal for munitions, but there was some scepticism as to whether they were actually used for this purpose. In Gainsborough, Derek and Shirley remember the iron railings being cut down for the war effort.

Derek Farr Oral history interview, 2018

Shirley Dawe Oral history interview, 2017

During the Second World War, many children living in big cities and towns were moved temporarily from their homes to places considered safer, usually out in the countryside. The British evacuation began on Friday 1 September 1939 and was called ‘Operation Pied Piper’. Between 1939 and 1945 there were three major evacuations in preparation of the German Luftwaffe bombing Britain. The first official evacuations began on September 1 1939, two days before the declaration of war. By January 1940 almost 60% had returned to their homes. A second evacuation effort was started after the Germans had taken over most of France. From June 13 to June 18, 1940, around 100,000 children were evacuated (in many cases re-evacuated). When the Blitz began on 7 September 1940, children who had returned home or had not been evacuated were evacuated.

Many children were evacuated to Gainsborough from the cities in the North such as Sheffield and Leeds or from places along the coast such as Hull. Derek Farr recalls children being evacuated to his village of East Stockwith and Marion Hird below remembers children arriving in the village of Morton.

Derek Farr Oral history interview, 2018

Marion Hird Oral history interview, 2015

The Second World War ended in 1945 and on 8 May 1945, the Allies accepted Germany’s surrender, about a week after Adolf Hitler had committed suicide. Victory in Europe Day celebrates the end of the Second World War and many street parties were held across Britain on 8 May 1945.

Marion Hird Oral history interview, 2015

John Goddard Oral history interview, 2015

Shirley Dawe Oral history interview, 2017

VE Day Party on Fairway Avenue (Phil Roberts)

VE Day Party

VE Day Party on Burns Street (Paul Wright)

In the aftermath of War Gainsborough like many towns and cities had to rebuild the town whether in the physical sense of bomb damage on Market Street or with their own family and the loss they may have suffered from loved ones who didn’t come back from the Front.

To finish this article Jim Page has an interesting story to tell about the Dambusters. He recalls seeing them regularly flying over on training missions at the house where he lived in Willingham-By-Stow.

Jim Page Oral history interview, 2017

Thank you for reading and listening.

References

- Gainsborough Heritage Association Oral History Archive, Derek Farr, Shirley Dawe, Jim Page, Joyce Thompson, Harry Barrett, Enid Burrell, Phyllis Peart, Norman Antcliff, John Goddard, Marion Hird and Rosemary Speck.

- Gainsborough At War 1939 to 1945 by John Norton